Tour of Britain: How cycling is helping flood-hit Cumbria recover – BBC News

As Cumbria nears the end of its slow recovery from last winter’s devastating floods, tourism bosses are looking at cycling as one way to attract visitors and show the county is “open for business”. The BBC’s Robert Greenall took a ride through the Lake District to see how its people and businesses have recovered.

On Monday the competitors in the Tour of Britain will ride through Cumbria, visiting areas that last year were devastated by some of the worst flooding seen for decades.

The county has long been an ideal spot for cyclists, boasting a wealth of picturesque and challenging routes which show off the beauty and grandeur of the Lakes.

Now the authorities are hoping to make use of the massive popularity of cycling to attract new visitors to the region and has opened a new route – the Lakes and Dales Loop.

It skirts around the Lake District before crossing over to the western edge of the Yorkshire Dales National Park.

Traffic-clogged main roads are avoided and beautiful but little-known areas of moorland such as Caldbeck Commons, in the northern Lakes, or the huge Birker Fell, in the south west, are introduced.

Image copyright John McFarlane

Image copyright John McFarlane  Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images Though other routes criss-cross the county, the Loop is the only one contained within Cumbria. As such, it is a journey that provides a unique insight into what the county has been through.

One of the communities it takes in is Cockermouth – a small, picturesque town that is no stranger to flooding, having been hit three times in the recent past.

After it was deluged in 2009, a “flood trail” was created so that tourists could see its effects. That flood was a huge blow to the town, but people came together to deal with what they thought was a once-in-a-lifetime event.

What they did not expect was that it would be repeated again so soon.

In December 2015, the waters came again. This time flood defences softened the blow for the town centre somewhat, but residential areas on the other side of the River Derwent were worse hit.

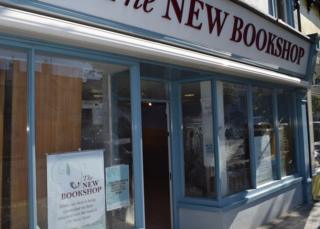

“It was hard the first time but we were all very optimistic it was a one-off, but now it’s happened again we’ve realised it could be the start of a pattern,” says Catherine Hetherington, owner of the New Bookshop, which is still in temporary premises.

Ms Hetherington points out that, while Cockermouth was a major focus in 2009, in 2015 the affected area was much larger, and it was competing for attention with more high-profile places such as Carlisle, Keswick, Kendal and Appleby.

The damage has been slow to repair and key high street businesses such as the bookshop and the four-star Trout Hotel were only expecting to reopen fully in August.

Ms Hetherington says that, thanks to lost stock and lost revenue both from the shop and the caf that was inside it, she has written off 2016 in business terms.

Cockermouth is one of the main population centres on the Loop, and was my first overnight stop.

All along the route, people explained how they were affected one way or another by the floods. Some are still feeling the effects.

‘Worried and scared’: Ray Milner, warden, Cockermouth Youth Hostel

I own a small house in Cockermouth. I have a small salary as site manager but the main work is voluntary. I rented out the house. It’s on the other side of the river – a lot worse affected this time, some say because flood defences in the town centre worked by sending water over to the other side.

By some spiteful bit of irony, my boss had come to see me early in December to tell me they were closing [the youth hostel] down at the end of October this year.

For me this was personally very upsetting – I’d worked in the YHA [Youth Hostels Association] for 40 years. I thought: Oh well, that’s life, there are a lot of people worse off than me, hey, I’ve got a house I can move into. Great, two days later it had five foot of gunk dumped into it, the garage was wiped away. It’s still not ready yet.

What do I do now? That property has now been flooded three times in 12 years. If I move into it, am I going to burst out in a panic sweat every time it even slightly rains? Is the place even sellable? The property might be worth almost nothing as it is.

I had difficulty insuring it after the 2009 floods. I have a mammoth great floods excess to cover when this is all over. Will they insure after that? I don’t know. I’m a bit worried and a bit scared.

While many had homes and businesses damaged, almost everyone suffered because of broken infrastructure and transport links.

Businesses lost trade because tourists (and sometimes locals) could not reach them, and farmers lost crops and livestock.

Sometimes the losses were small but significant.

One hill farmer in the south-western village of Ulpha, Charlie Hutchings, explained that he had paid 1,000 to fix the driveway to his farm which was washed away by the torrents, only to be told that he might not be eligible to claim the money back because the track is a public right of way.

Extra flood-induced costs are the last thing small, struggling farmers need, and many will have suffered much more than Mr Hutchings.

The end of the second day – one of enormous climbs and precipitous drops – brought me to Broughton-in-Furness, an attractive market town in the south-west corner of the Lakes.

The Furness peninsula was one area that escaped flooding, though it was completely cut off.

The A590, linking it with Kendal and Lancaster, was inundated for long stretches, affecting a whole swathe of southern Lakeland.

Ironically it was here that I realised just how unpredictable Lakeland weather can be. After a day of 28C heat, the next morning saw torrential downpours, forcing me to abandon my next foray into the fells and take a train instead.

I returned to the saddle a few miles further east once the storms had passed, where the Loop exits the Lake District.

It wasn’t just the Lakes that were hit.

Dales towns such as Kirkby Lonsdale and Sedbergh were flooded, though few people or buildings were affected.

But it was the River Eden in Appleby, which I rode into the following day, which caused one of the most severe shocks of that fateful few days last December, engulfing the town bridge and reaching areas that had never flooded before.

Many local traders were taken by surprise, unable to deal effectively with the speed and volume of water.

‘Running like a sea’: Yvonne Collins, Bojangles Bistro, Appleby

Image copyright Rebecca Collins/Facebook

Image copyright Rebecca Collins/Facebook I live on the other side the river. We got up on Saturday morning [5 December] – we knew it was bad but we’ve seen it bad before.

We could look down from our bedroom window and see the water higher and higher, going further and further up the graveyard [at the back of the caf] towards the church. You couldn’t get over the bridge, it becomes two separate towns.

I’ve seen nothing like it, it was Biblical, it was running like a sea. By the next day it was just unbelievable – a real shock.

The really good thing that came out of it was how the town, and friends, helped. I turned up on Monday and there were people from all over. Whether they were affected by the flood or not, every single person helped.

The tourists are interested. I think they’re more bemused than anything else because when they look at the river now, and there’s no water in it, they think – how the hell did it get so deep so far away from the river?

Some were unable to reach their businesses as the loss of the bridge meant the town was cut in two. It was restored only two weeks later, and for that time residents on the other side faced a 30-mile detour to get into town.

“It was a 1 in 300-year event, cataclysmic. Water never got anywhere near us before,” says Nigel Milsom, owner of the Tufton Hotel.

The hotel, which is in the main town square, only had water up to its front step, but was undone by a series of air vents at ground level which Mr Milsom had not known about.

Water filled the cellar, undermining the floors and joists. The resulting damage closed the hotel for three months.

In the end, many businesses were closed until Easter or beyond.

Mr Milsom said the hotel was finally getting back to normal after a slow spring and early summer.

And that seems to be the picture across town. Many spoke of a strong community working hard to get back to normal.

Perhaps surprisingly, some local businesspeople spoke highly of their insurance companies, saying prompt and generous payouts had really helped them recover relatively quickly.

One other factor has given the town a boost.

Two months after the floods, a landslide closed part of the Settle to Carlisle railway, causing trains to terminate in Appleby. Many visitors travelling up from Yorkshire preferred to stop in the town rather than take the replacement bus on to Carlisle.

“Sometimes on a Saturday we’d get 200 people come down after we’d opened [in April] – which was fabulous because we needed to make up the business,” says Yvonne Collins, owner of Bojangles bistro.

A few people are still waiting to return to their flooded homes, but on the whole Appleby has bounced back from last December’s catastrophe.

Cumbria as a whole may still have some way to go.

The Lakes and Dales Loop

- A reworking of the old Cumbrian Cycleway, it starts and finishes in Penrith and consists of nearly 200 miles of undulating – and often steep – terrain.

- It takes about one to six days to complete, depending on fitness

- Goes through attractive market towns such as Broughton-in-Furness, Kirkby Lonsdale, Sedbergh and Appleby

- Passes several cycle-friendly community cafes and shops along the way, notably Greystokes cycle cafe, Gather in Ennerdale Bridge and the Church Mouse in Barbon

- As the route goes around the edge of the National Park, none of the major lakes are on it, although there are glimpses of a few and the route does go alongside Loweswater and Overwater, two very picturesque smaller lakes

- After skirting the western and southern boundaries of the Lake District, the Loop heads east towards the Dales. Here you can go for miles without seeing a single car, on roads which are basically just two tracks of asphalt hemmed in by nettles on either side

- After Kirkby Lonsdale, it goes through Barbon Dale, very popular with cyclists, and the remote, unspoilt and utterly lovely Dee Valley

Read more: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-cumbria-36885273