The reality of being black in todays Britain | David Olusoga

David Olusoga grew up amid racism in Britain in the 70s and 80s. Now, in a groundbreaking new book and TV series, he argues that the story of black Britons, from Afro-Roman times to the present, is key to showing the depth of their Britishness. And, while we exult in black Britons success in culture, fashion and sport, discrimination still blights their lives

When I was a child, growing up on a council estate in the northeast of England, I imbibed enough of the background racial tensions of the late 1970s and 1980s to feel profoundly unwelcome in Britain.

My right, not just to regard myself as a British citizen, but even to be in Britain, seemed contested. Despite our mothers careful protection, the tenor of our times seeped through the concrete walls into our home and into my mind and into my siblings minds. Secretly, I harboured fears that as part of the group identified by chanting neo-Nazis, hostile neighbours and even television comedians as them we might be sent back. This, in our case, presumably meant back to Nigeria, a country of which I had only infant memories and a land upon which my youngest siblings had never set foot.

To thousands of younger black and mixed-race Britons who, thankfully, cannot remember those decades, the racism of the 1970s and 1980s and the insecurities it bred in the minds of black people are difficult to imagine or relate to.

But they are powerful memories for my generation. I was eight years old when the BBC finally cancelled The Black and White Minstrel Show. I have memories of my mother rushing across our living room to change television channels (in the days before remote controls) to avoid her mixed-race children being confronted by grotesque caricatures of themselves on prime-time television. I was 17 when the last of the touring blackface minstrel shows finally disappeared, having clung on for a decade performing in fading ballrooms on the decaying piers of Britains seaside towns.

I grew up in a Britain in which there were pictures of golliwogs on jam jars and golliwog dolls alongside the teddy bears in the toy shop windows. One of the worst moments of my unhappy schooling was when, during the run-up to a 1970s Christmas, we were allowed to bring in our favourite toys. The girl who innocently brought her golliwog doll into our classroom plunged me into a day of humiliation and pain that I still find painful to recall, decades later.

When, in recent years, I have been assured that such dolls, and the words golliwog and wog, are in fact harmless and that opposition to them is a symptom of rampant political correctness, I recall another incident. It is difficult to regard a word as benign when it has been scrawled on to a note, wrapped around a brick and thrown through ones living-room window in the dead of night, as happened to my family when I was 14. That scribbled note reiterated the demand that me and my siblings be sent back.

In the early 21st century, politicians in Whitehall and researchers in thinktanks fret about the failures of ethnic-minority communities to properly integrate into British society. In my childhood, the resistance seemed, to me at least, to come from the opposite direction. Many non-white people felt that while it was possible to be in Britain it was much harder to be of Britain. They felt marked out and unwanted whenever they left the confines of family or community.

It was a place and a time in which black meant other and black was unquestionably the opposite of British. The phrase black British, with which we are so familiar today, was little heard in those years. In the minds of some it spoke of an impossible duality. In the face of such hostility, many black British people, and their white and mixed-race family members, slipped into a siege mentality, a state of mind from which it has been difficult to entirely escape. What drove us deeper into that citadel of self-reliance and watchful mistrust was not just racial prejudice but a wave of racial violence.

Throughout those embattled years, my mother, somehow, managed to maintain within our family a regime of self-education and self-improvement. It was this internal, familial microculture that slowly drew me to read history. I stumbled upon the subject that was to become my vocation out of a simple love of story and because of a gung-ho fascination with the Second World War that was almost obligatory among boys of that period, whatever their racial background.

The racism that had so deeply affected our lives was given a historical context

Britain in the 1980s was a nation still saturated in the culture and paraphernalia of that conflict. For the white working-class community that I grew up in, the war was the most exciting and significant event ever to collide with our terraced streets and decaying factories. It had changed the lives of my white grandparents, whom I loved deeply, and I was intoxicated by the thought that German bombers had prowled the skies above my home town and that my grandfather had scanned those skies while on watch on the roof of the Vickers Armstrong factory by the Tyne, where he worked building tanks. I wandered into history looking for excitement.

I never expected that there I would encounter black and brown people who were like me and my family. I was alerted to those stories of presence and participation by my white mother and I stumbled across more and more stories of black British people as my interests took me further back, into the 19th and then the 18th century.

In 1986, I came across the book Staying Power by the British journalist Peter Fryer. It was, I believe, the first book I ever bought for myself. This history of the black presence in Britain was published in 1984, the year in which my family had been besieged in our home, and it set the racism that had so deeply affected our lives within a historical context. It allowed me to understand my own experiences as part of a longer story and to appreciate that in an age when black men were dying on the floors of police cells, my own encounters with British racism had been relatively mild. For me and for thousands of black and white people who read Fryers book, its effect was transformative. Fryer took his readers back through the centuries and introduced us to an enormous pantheon of black historical characters, about whom we had previously known nothing.

Those black Britons have been with me ever since. I have visited their graves and read their letters and memoirs. They have become part of British history and in some cases part of the national curriculum.

Staying Power remains a uniquely important book and anyone who has ever written about black history has found themselves referencing it, quoting from it or seeking out some of the myriad of primary sources it drew together. Fryers eloquent chapters offer guidance and provide orientation through a complex and fractured history. Although not the first work of black British history, its impact spread further than most, in part because its publication came at a crucial moment, three years after a wave of riots sparked by hostile policing set ablaze black neighbourhoods of London, Bristol and Liverpool.

There was a terrible symmetry to the fact that the most serious and sustained of the early 1980s riots took place in the cities from which the slave-traders had set sail in the 17th and 18th centuries. Cities that had been enriched by the slave trade and the sugar business saw fires set and barricades erected by young people who were the distant descendants of those human cargos. Not far from the flickering flames of the Bristol riots, a statue of Edward Colston, a slave trader and member of the Royal African Company in the 17th century, looked on as the police were driven out of the black St Pauls district.

The riots of the early 1980s were profoundly different from the disturbances of 1919, 1948 and 1958, all of which were at various times described as race riots but were mostly outbursts of violence in which white gangs targeted black people and communities. This was not the case in the 1980s. These riots have been called uprisings.

They were fought by young black people in response to years of systematic persecution and prejudice. They were destructive and damaging but they were understandable. While it is clear today that the riots marked the beginning of the end of one chapter, the nature of the new age that followed remains to be seen.

The 1990s and the 2000s were, in many ways, better days. Survey after survey plotted the decline of racist sentiment as a younger generation emerged who had not experienced the racism of the postwar period nor been brought up to view the world in racial terms. Yet this period was the era in which the name of Stephen Lawrence was added to the long list of black Britons who have been murdered by racists.

Historians tend to be cautious when it comes to commentating on the modern age, the period through which we are currently living. For me, the period from the 1980s onwards is the one I know from personal memory as well as through historical study, which probably clouds more than it clarifies judgment. But I strongly recall that in the 1980s there was a strong sense among black people of being under siege and of feeling the need to fight for a place and a future in the country. One of the ways in which black people, and their white allies, attempted to secure that future was by reclaiming their lost past.

The uncovering of black British history was so important because the present was so contested. Black history became critical to the generation whom Enoch Powell could not bring himself to see as British. A history was needed to demonstrate to all that black British children, born of immigrant parents, were part of a longer story that stretched back to the Afro-Romans whose remains are only now being properly identified.

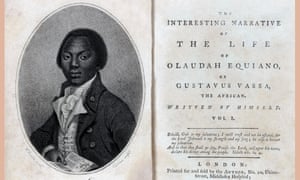

It was in the 1980s that the concept of Black History Month was brought to Britain, an idea that had been pioneered in the United States back in the 1920s, as Negro History Week. Black History Month was needed in Britain because the black past had been largely buried and it was during the 1980s that the task of exhumation took on real urgency. Unusually, history became critical to a whole community, while at the same time becoming highly personal to those who discovered it. To look at the portrait of Olaudah Equiano for the first time, and stare into the eyes of a black Georgian, was, for me, as for many thousands of black Britons, a profound experience. To see Equiano, with his cravat and scarlet coat, was to feel the embrace of the past and of a deeper belonging.

The black British history that was written in the 1980s was built on the foundations of earlier scholars such as James Walvin and was expanded by hundreds of committed volunteers; local historians, community historians and brilliant, determined, sometimes obsessive amateurs. Most worked and still work outside of academia, producing local history or uncovering the presence of black people in parts of the British story from which they have been expunged the world wars, the history of seafaring, the world of entertainment and many others.

It is hard to believe that without the recent decades of black history research and writing, the nation, in 2007, would have committed 20m to commemorate the bicentenary of the abolition of the slave trade. A sum that matched, by chance, the price the nation had paid the slave owners in compensation for the loss of their human property in 1838. The next step, I contend, is to expand the horizon and reimagine black British history as not just a story that took place in Britain, and not just as the story of settlement, although it matters enormously.

From the 16th century onwards, Britain exploded like a supernova, radiating its power and influence across the world. Black people were placed at the centre of that revolution. Our history is global, transnational, triangular and much of it is still to be written. The opening ceremony of the 2012 London Olympics, a vast, globally televised pageant that celebrated the British national story, which revelled in the nations diversity, music and pop culture, included a mock-up, miniature Empire Windrush. This replica was made of a metal frame around which had been stretched fabric printed with the covers of hundreds of postwar British newspapers.

She appeared in the Olympic stadium as one among a series of symbolic representations of the pivotal events in British history: the Industrial Revolution, the First World War, the campaigns of the suffragettes, the Jarrow march of 1936 and the creation of the NHS in 1948, the year the Windrush docked at Tilbury. Britains black population today stands at around two million, a little more than 3% of the national total. There had been, at most, a few thousand black Londoners in 1948. The history symbolised by the Windrush has become a part of the British story, in a way that no one who attended the 1948 Olympic Games could have possibly imagined.

The Empire Windrush has entered the folklore and vocabulary of the nation. There is a Windrush Square in Brixton, a heritage plaque in Tilbury marks the spot where the ship docked and the West Indian migrants came ashore, and a musical based on the lives and ambitions of the Windrush migrants enjoyed a successful run in Londons West End. But this triumph of remembering has come at a cost. The symbolic power of the Windrush moment has at times obscured the deeper and longer black history.

Britain has undergone a second great wave of black migration

As well as losing sight of the more distant past, our focus on the postwar story has meant that, at times, we have been slow to recognise more recent changes. Since the start of the 1980s, Britain has undergone a second great wave of black migration, one that has largely gone unnoticed. This new influx lacked a single iconic moment, comparable to the docking of the Windrush in 1948, and it took place in the far less romantic settings of Gatwick and Heathrow airports, but it was in those great hubs of modern air travel that thousands of Africans arrived, despite ever stricter immigration laws.

At the turn of the century, West Indians still made up the majority of the UKs black population. But, as the 2011 census revealed, between 2001 and 2011, the British African population doubled, through both migration and natural increase. For the first time, probably, since the age of the Atlantic slave trade, the majority of black Britons or their parents have come to this country directly from Africa, rather than from somewhere in the Americas.

The migrants from West Africa were mostly Nigerians and Ghanaians and tended to be a little wealthier than the West Indians who had come before them, but were certainly not wealthy by global standards. Some came initially to study but ended up staying. Others migrated to join family and set up home or to take up employment in a Britain that was still hungry for skilled workers. Many of those who arrived from Somalia, Zimbabwe and Sudan came as refugees.

The long queues at Britains airports of British Africans travelling to Accra, Freetown or Lagos to attend family reunions, weddings or funerals speak to the strengths of the new connections between Britain and Africa. The great postwar project to build an English-speaking, multiracial Commonwealth with London at its heart, a community of willing nations led by statesmen and businessmen, has, in a sense, been overtaken by globalisation and unprecedented levels of world migration. In a form that the politicians of the 1940s did not envisage, London remains at the centre of the former empire. The capital has become a node in a vast global network of family connections, remittances, investment and mobility. Despite the questionable attractions of nearer Dubai, millions of Africans still feel powerfully drawn to London.

While the British African population expands, the West Indian population, longer established and more fully integrated, has amalgamated and assimilated more successfully than perhaps any other immigrant group of modern times. The remarkable capacity of West Indian immigrant families to assimilate can be seen in the marriage statistics. Fewer than half of British West Indians have partners who are also West Indian. According to the Economist, a child under 10 who has a Caribbean parent is more than twice as likely as not to have a white parent.

While West Indians have drawn millions of white British people into their family networks, they and the African migrants have drawn the whole nation towards their cultures and music. Through sports, music, cinema, fashion and (only latterly) television, black Britons have become the standard bearers of a new cultural and national identity, the globalised hybrid version of Britishness that was so successfully and confidently expressed in 2012.

These successes and achievements have been remarkable and in many ways unexpected. The problem is that these good news stories can at times become window dressing and inspire wishful thinking.

The reality is that disadvantages are still entrenched and discrimination remains rife. A report by the Equality and Human Rights Commission published in August showed that black graduates in Britain were paid an average 23.1% less than similarly qualified white workers. It revealed that since 2010 there had been a 49% increase in the number of ethnic minority 16- to 24-year-olds who were long-term unemployed, while in the same period there had been a fall of 2% in long-term unemployment among white people in the same age category.

Black workers are also more than twice as likely to be in insecure forms of employment such as temporary contracts or working for an agency. Black people are far more often the victims of crime. You are more than twice as likely to be murdered if you are black in England and Wales, said the report, starkly. When accused of crimes, black people are three times more likely to be prosecuted and sentenced than white people.

When, as a young man, I began to study history I came to see it as a way to understand the forces that had brought my parents together, shaping my own experiences. Like millions of others, I am a product of Britains long involvement with Africa: a history of slave trading and colonisation, but also of traders, missionaries and the Saro people who, having been liberated from slave ships by the Royal Navy, returned to Nigeria from Sierra Leone, bringing to Lagos the city of my birth their Anglican faith and their hybrid Anglo-African identity.

My parents were able to meet in the Britain of the 1960s due to links that had been established in the late 19th century between communities, schools and churches in Lagos, Sierra Leone and other parts of West Africa and universities in the north of England. The racist attacks that, two decades later, led to me and my family being driven from our home by thugs inspired by the National Front were a feature of another inescapable aspect of that same history the development and spread of British racism.

The walls of disadvantage that today block the paths of young black Britons are a mutated product of the same racism. Knowing this history better, understanding the forces it has unleashed, and seeing oneself as part of a longer story, is one of the ways in which we can keep trying to move forward.

This is an edited extract from David Olusogas Black and British: A Forgotten History (Pan Macmillan, 25). The book is based on a BBC series of the same name, which begins on BBC2 on 9 November at 9pm. To order a copy of the book for 20.50, go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846

Read more: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/oct/30/what-it-means-to-be-black-in-britain-today