Street art: Crime, grime or sublime? – BBC News

Street art is hard to avoid, even if you want to. It creeps along alleyways, blooms across fences, flourishes on flyovers and in underpasses. It’s an age when you can awake in the morning to find your house value increased overnight with the emergence of a Banksy on your wall – or even something a bit like a Banksy on your wall.

Public perception appears to have changed.

People used to scrub the art away, but nowadays the first reaction seems to be “is it worth money?”

Street artist Neil Morris agrees this is the case with some, but “these are the people who never have and never will appreciate the work.

For more street art stories follow us on Pinterest

“These people are middle-aged, middle-manager types that think the art is offensive to others without actually asking anyone. And it’s money that has changed perception. Money changes everything.”

Image copyright Matt Cardy

Image copyright Matt Cardy  Image copyright GEOFF CADDICK

Image copyright GEOFF CADDICK  Image copyright JEFF OVERS

Image copyright JEFF OVERS

Fellow artist Jadryk Brown argues that the high prices street art can fetch means “rich people don’t find it scary any more. Nothing’s scary if money could be involved”.

The internet has also been an influence, according to Richard Clay, professor of digital humanities at Newcastle University.

“These images can, and sometimes do, go viral. For example, the painting and then defacement of a mural of Putin kissing Trump in Lithuania.

“In some cases a photo of a piece of street art online can simply be picked up and adopted in another place. For example, during the Arab Spring, images of Assad with a Hitler moustache appeared online and could soon be seen in Cairo, Beirut and Gaza.

“The ready availability of examples of street art from across the globe informs the practice of artists and the views of their audiences.”

He speculates that “the authenticity, the site specificity and the (usually) one-off nature of street art” might “serve as an antidote to the super-abundance of online images and to streets that are often cluttered with mass-produced commercial imagery”.

Image copyright Matt Cardy

Image copyright Matt Cardy  Image copyright JEFF OVERS

Image copyright JEFF OVERS  Image copyright OLI SCARFF

Image copyright OLI SCARFF  Image copyright Banksy.co.uk

Image copyright Banksy.co.uk

A study from the University of Warwick indicates that street art in London is generally now associated with improving economic conditions of urban neighbourhoods.

It’s partly down to a “loop effect”. Arty areas – such as Brixton – attract more cafes and restaurants that in turn attract the art-loving crowd to move in.

Areas outside London can also see graffiti affecting property prices – in both directions.

Prof Clay says it can polarise opinion: “To most people street art is either an indicator of an area that is vibrant or of one that is run-down and in need of better policing.

“It very much depends on individuals’ broader opinions about acceptable behaviours in public space, but it seems clear to me that more and more people regard street art as a positive phenomenon.

“Hence, it appears to be being more widely tolerated by public authorities.”

Drawing on walls in public places isn’t a new phenomenon. From the prehistoric cave paintings of Burgundy in France, through gladiatorial fan worship in Roman Lyons to the messages left on the walls of Germany’s Reichstag in 1945 by triumphant Soviet troops, people are determined to leave a record of their existence and experience.

Nor is it an activity associated with one particular socioeconomic group, says Prof Clay.

Image copyright Dan Kitwood

Image copyright Dan Kitwood “Historically it isn’t the case. For example, in Rome you can see graffiti left over centuries by aristocratic visitors to the Eternal City.

“There is a tendency nowadays to see modern graffiti as being a working class, inner-city phenomenon. While that has been and remains the case in some cities and with some graffiti writers and crews, it often isn’t the case.

“The creative urge to leave one’s mark in public space crosses the boundaries of class, gender, sexuality, ethnicity and religion. It always has and it always will.”

Artist Scotty Brave points out there has always been graffiti that was thought-provoking, political and clever.

“Modern times have seen graffiti become many different things. Vandalism, art, politics, subcultural visual communication, cryptic language, esoteric social commentary, street art. Even a visual form of humour.

“So when you talk about graffiti, you are talking about all these things. All these things are different, their practitioners are different. Their motives are different, their methods, reasons, approach and application are all different veins of the rebellious act of graffiti.

“Has it lost its power? Of course not, no way, how can it? What power did it ever have?

“The power is in the perception, it’s generated by the observer. It can lose power if it allows itself to be generalised, to be boxed, to be spoken of as if it’s understood, contained, conquered by those who attempt to categorise, water down and generalise it.

“So be very careful what you say or what you write about it.”

Image copyright IAN NICHOLSON

Image copyright IAN NICHOLSON  Image copyright John Giles

Image copyright John Giles  Image copyright Jim Dyson

Image copyright Jim Dyson So is there “good” graffiti and bad? Prof Clay says “good graffiti doesn’t have to be aesthetically sophisticated”.

“My favourite recent example is visible on a motorway bridge heading north up the M6. In messy, white, blocky paint it reads ‘Pies this is your time’. Like many Lancastrians, I love pies and it made me smile and think of home. It took me a long time to realise that The Pies are actually a band.”

Scotty Brave insists graffiti “has always been art. Even if it’s arguably so. I’ve seen a slashed canvas and a urinal in an art gallery.

“Why not a crude penis scribbled on a police station’s window, or a spray-painted name on a train’s door? It’s all art.”

But some residents in Marlborough, Wiltshire, contacted the BBC to complain about some street art that appeared on a junction box in the town.

Kate Tudor says: “Graffiti is vandalism. I still have to pay to have it removed. Why do you assume everyone has a right to express their stuff by painting on public walls? Why would the rest of us be interested in the thoughts of one special snowflake?”

And fellow townsperson Josh Hartshorn argues: “Art is something you choose to see and pay for in your house and graffiti gives you no choice and you have to pay to not look at it.”

Some local authorities have been keen on promoting street art – in 2012 Bristol City Council supported an “urban paint festival” featuring graffiti, while also clamping down on tagging.

Now in its eighth year, the organisers of Upfest say it is “Europe’s largest free, live street and urban art festival”.

Image copyright Geograph

Image copyright Geograph Callington in Cornwall has murals throughout the town, which are promoted by the town council as a trail for tourists.

But other local authorities don’t always see the merit of street art – a council that destroyed a mural by Banksy in Clacton-on-Sea was branded “moronic”, “useless” and “cretinous” by members of the public after painting over a stencil showing a group of pigeons holding anti-immigration banners towards an exotic-looking bird.

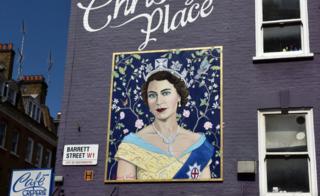

If street art can be used as a form of protest or social commentary, it can also be used as a celebration.

Six murals were commissioned to mark Leicester City’s unlikely Premier League title triumph.

Each design captures a different aspect of the Foxes’ remarkable win.

There’s a fine line, though, between appreciating street art and taming it. It’s becoming more common for images to protected in situ with thick pieces of Perspex, or even jimmied off walls and reconstructed in galleries, such as the Banksy work removed from a car park in Liverpool.

Sam Fishwick, a graffiti artist from Liverpool, dismissed the idea of a street art gallery.

“It’s not street art any more if it’s hung up in a museum.

“It’s raw, it’s gritty, it’s on the street, it’s not meant to be there. When you go and see it in a gallery it loses its charm, it loses its character.”

Artist John Doh agrees: “When a piece is taken from the street and put inside a museum or gallery it can be a real killer. Often the placement is just as important as the piece.”

Scotty Brave says articles attempting to answer questions about street art “are futile”.

“The difference is in the painter – whether it’s the artist, the activist, the writer, the vandal, the illustrator. People’s perception is changed by how it is communicated. It’s a visual language, with many tongues, many accents and forms.

“Articles written by people who attempt to group all the genres of graffiti together as something that can be talked about as one thing are futile. It’s not one thing, it’s many. It cannot be boxed or labelled so easily.”

So perhaps the only thing street art tells us about a place – is that it can tell us nothing.