Sex Pistols: Anarchy in the UK and the tour they tried to ban – BBC News

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images Exactly 40 years ago the Sex Pistols were due to begin a 19-date UK tour to promote their new single Anarchy in the UK. Today the tour is remembered as a key moment in music history – as much for what didn’t happen as for what did. In the furore that followed the band’s appearance on TV show Today with Bill Grundy, all but a few of the gigs were cancelled.

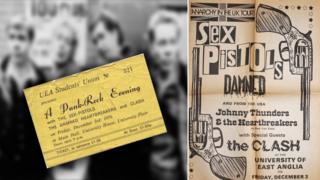

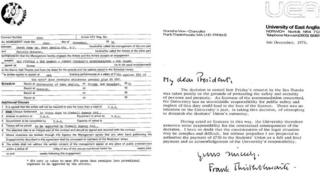

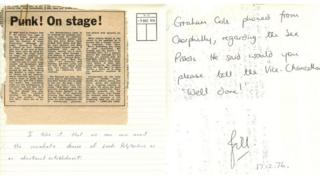

The first show was due to be held at the University of East Anglia (UEA) in Norwich on 3 December 1976. Billed as a “A Punk-Rock Evening”, tickets cost 1.25 in advance and 1.50 on the door, but collectors would pay many times that for one now. The concert never went ahead: earlier that day, vice-chancellor Dr Frank Thistlethwaite banned it “on the grounds of protecting the safety and security of persons and property”.

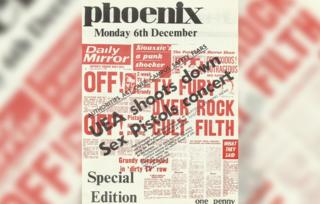

Two days earlier, the Pistols – lead singer John Lydon (aka Johnny Rotten), guitarist Steve Jones, bassist Glen Matlock and drummer Paul Cook – appeared as late replacements for EMI labelmates Queen on Today, a live London regional TV show. When presenter Bill Grundy contemptuously encouraged them to swear they duly obliged, damaging his career while catapulting themselves to notoriety.

The subsequent national newspaper headlines and ensuing moral panic led venues, under pressure from councils, to cancel gigs by the Sex Pistols, fearing violence, vandalism and who knows what else.

Image copyright Punk in the East

Image copyright Punk in the East  Image copyright UEA

Image copyright UEA  Image copyright UEA

Image copyright UEA  Image copyright UEA

Image copyright UEA Upon hearing of the cancellation of the Norwich gig, 50 students occupied the university’s administration block in protest at “a direct attack” on the student union’s autonomy. Dr Thistlethwaite later offered the union 750 from UEA funds to cover its losses.

Even as gigs were being cancelled, the band – and support acts – continued to travel the country hoping to play, or at least collect their fee. In his book I Was a Teenage Sex Pistol, Matlock writes: “The major memory of the tour is boredom. We spent most of our time hanging around hotels, just waiting.

“As gig after gig was cancelled, we had no idea of what would happen next – or what was happening at the time. We’d just sit around hoping they could find somewhere we would be allowed to play.”

Only three of the scheduled gigs went ahead, along with four other rearranged shows. The tour finally started at Leeds Polytechnic on 6 December, with further dates at Manchester’s Electric Circus (9 and 19 December), Caerphilly’s Castle Cinema (14 December), Cleethorpes’ Winter Gardens (20 December) and Plymouth’s Woods Centre (21 and 22 December).

The Caerphilly gig was picketed by carol-singing Christian protesters – “religious maniacs”, in Matlock’s words – while he remembers a bottle of brown ale being thrown at him at the Electric Circus. “That could easily have killed me,” he writes.

Image copyright YouTube

Image copyright YouTube  Image copyright Jonny Edwards

Image copyright Jonny Edwards  Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images At both Manchester gigs was Ian Moss. Then 19, he had already seen the Pistols play twice that summer. This included the legendary 4 June date at the city’s Lesser Free Trade Hall, whose tiny crowd included Peter Hook and Bernard Sumner, who went on to found Joy Division, plus Morrissey and members of Buzzcocks.

“It was completely life-changing”, says Mr Moss of that gig. “The Pistols walked on stage and it was magnetic. I had not seen people who looked liked that. They started playing and it was exciting – the music was really good – but the main thing was the attitude. I had seen David Bowie and Mick Jagger but he (Lydon) had more charisma than either of them.”

Six weeks later, he saw the Pistols play to a much larger crowd there. “Somehow it left me feeling a bit detached. They didn’t have to try to win the crowd over, but I still thought this band was absolutely wonderful.”

The December gigs were at the Electric Circus in Collyhurst, “a really rough part of Manchester”. Mr Moss remembers “packs of blokes going round beating anyone who looked like they might have been going”, adding: “Even inside, you weren’t safe.”

Image copyright Ian Moss

Image copyright Ian Moss  Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images For the first time, he saw lots of people dressed in “punk” styles. “Back in the summer, nobody apart from the people who had travelled up from London looked like punks, but by December people had made the effort.”

The Damned, one of the original support acts, had been thrown off the tour, so local boys Buzzcocks stood in. Mr Moss’s verdict? “Magnificent.” Next came The Clash: “Really great.” Then Johnny Thunders and the Heartbreakers. “Wow! Just so good.”

Finally, the Sex Pistols. “They were energised by it all; they were ferocious. It was all exciting. There was a big crowd but I still got the nagging feeling that too many people there were impostors and it spoilt it for me.”

The Pistols returned 10 days later, and so did Mr Moss, this time part of a much smaller crowd. “Everybody had wanted to see them, but once was enough for a lot of people. As John came on stage he peered into the crowd and said ‘I see we have lost some of the tourists.’

“The consensus is the Pistols coasted and were sloppy that night, but I beg to differ – it was the best I ever saw them.”

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images  Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images Now approaching 60 and a musician himself, Mr Moss cites punk and the Pistols as “pivotal” in his life.

“Right from the start I sensed there was more to it than good-time music. It was about questioning things and having the courage of your convictions.”

But what was it like to have actually been a Pistol? Asked his memories of the tour today, Matlock says: “I try not to think about it. Blokes like me are trying to move on.”

Understandable, perhaps. His time with the Pistols – he left in February 1977 – is only a tiny part of a long career, working with artists including The Faces and Iggy Pop. He has just finished a nationwide tour with his band The Philistines and has new solo material out next year.

Nevertheless, he understands the interest in nostalgia. “People move on but it’s the nature of the world to keep looking backwards,” he says.

Image copyright Fiona Garden

Image copyright Fiona Garden To illustrate his point, he recounts a conversation he had during an intimate medical examination a few years ago.

“The camera was up there just about as far as it could go. The doctor could see I was a bit nervous, and, without giving any indication he knew who I was, said: ‘So, what was Johnny Rotten like, then?’.

“I just said ‘There’s a time and a place, mate.”

Matlock says he found the Anarchy tour frustrating, as well as boring. “The whole reason I wanted to be in a band was to be a musician but we weren’t allowed to play.

“We was all very young and we’d just had the backlash from the Bill Grundy show. We were back and forth across the Pennines, followed all the way by the press in the days when they still had ‘Press’ in their hatbands. It was like being in a goldfish bowl. It was odd. We weren’t rocking and rolling every night.”

He now views the tour as “a necessary evil – something that had to be done”, and feels the tensions within the Pistols that it exposed ultimately led to the band’s demise, prior to their reformation in the 1990s.

Did he ever think people would still be talking and writing about them, 40 years later? “No, I never thought past the end of the week,” he says.

“It’s something I’m proud of, but it’s probably better looking in than out.”

The band’s impact has been felt far beyond music, though. Indeed the establishment that once railed so furiously against the Pistols now often consists of the band’s fans.

This is certainly true at UEA – where the Anarchy tour hit its first hurdle on its opening night.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images John Street, a professor of politics at the university, was a punk-loving PhD student at Oxford in 1976 and now teaches students about the movement.

“Punk was quite a disruptive and shocking moment, and it remains part of the history and landscape of British politics still,” he said.

“John Lydon publishes his second autobiography and he’s interviewed on the Today programme and Newsnight,” he added.

“Why is he being taken so seriously? Because, for some people, he was an icon of their youth and remained part of their personal biography.”

While 40 years ago, the UEA authorities may have believed Lydon when he sang “I am an antichrist”, it seems they no longer do.

Current vice-chancellor Prof David Richardson has written to him, reminding him of the anniversary and confiding: “The punk scene played a large part in my life as a younger man.”

Noting that Lydon spent time in Norfolk as a boy, developing a soft spot for Norwich City, Prof Richardson also enclosed a Canaries bobble hat.

There was another gift, too: a UEA library card. “Your book Anger is an Energy also vividly brings to life just how important education, books, learning and libraries were to you as a child,” he writes.

“Unlike in 1976 you are very welcome to visit UEA again to use our university library. If you are ever passing through Norwich again with Public Image Limited, I’d be delighted to show you round.”

So what was the reaction of the man once deemed too dangerous to play? The university has yet to receive a formal reply, but a spokesman said: “I did get a text saying ‘he absolutely loved it’.”

Read more: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-norfolk-38165091