Operation Julie: How I infiltrated a drugs gang – BBC News

Image copyright Stephen Bentley

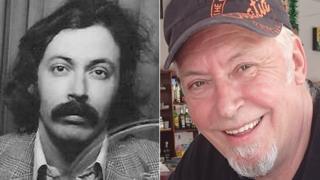

Image copyright Stephen Bentley At the age of 29, Stephen Bentley, a fresh-faced detective, turned himself into Steve Jackson, a dope-smoking, hard-drinking hippy. His time spent undercover with a gang making and distributing LSD helped bring down two criminal networks – but ultimately at huge personal cost to himself.

The drugs ring he infiltrated for two years in the mid 1970s had its origins in the counter-culture of the 1960s. It involved doctors, scientists and university graduates.

Liverpool University chemist Richard Kemp had been recruited in 1969 by Cambridge author David Solomon to manufacture LSD, initially at least as part of a social experiment to bring about world peace through “mind-expansion”.

They turned to London businessman Henry Todd to handle sales, but by 1973 the group had fallen out, and Kemp and Solomon moved production from Cambridge to west Wales, creating two distinct networks.

In 1975 police were alerted when evidence of hydrazine hydrate, a key ingredient in the manufacture of LSD, was found in a Range Rover belonging to Kemp after it was involved in a fatal crash near Machynlleth, in west Wales.

An operation was set up to smash the drugs network. It was run in secrecy by Operation Commander Dick Lee, as a precaution against corruption in the Metropolitan Police and loose tongues in provincial police stations.

Mr Bentley was handpicked for the potentially dangerous undercover mission by Commander Lee, who regarded the young Liverpudlian as a “talented, friendly and intelligent detective”.

Although, as Mr Bentley now recalled, there was “no training manual” for infiltrating a drugs cartel.

His first operation was watching Plas Llysyn – an imposing mansion house deep in central Wales, where Kemp and his girlfriend, Dr Christine Bott, were suspected of producing LSD.

Although most surveillance was “utterly boring”, a decision was made to surreptitiously break into the property. It meant a trip to the local Woolworths to buy house breaking tools – hammers, screwdrivers and rubber gloves.

This covert break-in provided evidence of an acid factory in the cellar.

In June 1976, Commander Lee’s next plan was for Mr Bentley, along with fellow officer Eric Wright, to infiltrate what appeared to be a community of drop-out hippies, who lived in the village of Llanddewi Brefi. One individual – Alston Hughes, known as Smiles – was a key figure in LSD distribution.

They were given fake IDs – Steve Jackson and Eric Walker – and a cover story of auctioning second-hand cars. They also claimed to be searching for a lost brother who had absconded from court and joined a hippy commune in Wales.

Faded jeans and cheesecloth shirts became their uniforms. The pair stopped shaving and cutting their hair and lived out of the back of a Transit van – with some psychedelic flowers painted on the side, to add to the flower-power hippy image.

“I had a job to do but I was getting good money, and living a carefree life,” says Mr Bentley. “I was able to throw off the shackles of being Stephen Bentley and become a completely different person, with a different outlook on life, different standards, and different scenery.

“The freedom in itself was a high. It was exhilarating.

“Who was Steve Jackson? He was really me in a live stage play, but instead of being in the West End it was real life.”

Image copyright Stephen Bentley

Image copyright Stephen Bentley However, that level of freedom was not without cost. A “constant, unrelenting awareness” of the vital importance of not being found out – both for the importance of the operation and his own personal safety – piled pressure on him.

On top of that, the officers had virtually no contact with their families back home.

“My cover of being a used car dealer enabled me to get home to my wife for a day or two every so often but I was forced to hide indoors. People would have asked too many questions about the radical change in my appearance.”

When it comes to what attributes are needed to be a successful undercover officer, Mr Bentley is quite clear.

“The first quality is to be likeable. That breaks down most suspicions. I don’t think many people believe a police officer is capable of being a genuinely nice guy while the second is to be prepared to be reckless and take ‘them’ by surprise.”

In order to fit in as Steve Jackson, Mr Bentley had to adopt new habits, and that included taking drugs.

“The over-riding feeling was fear. I was worried about smoking dope and taking cocaine, but those fears subsided as I took more and didn’t end up in the gutter,” he said.

Operation Julie 1976-77

- Involved more than 800 officers from 11 forces in one the UK’s biggest ever anti-drugs operations

- On the 26 March 1977, 120 suspects were rounded up in raids across England and Wales, including chemist Richard Kemp, and distributor Henry Todd

- It smashed two LSD production and distribution networks thought to have been supplying up to 90% of the UK’s market in the drug

- One million LSD tablets were seized, along with enough crystal to make 6.5 million more

- After a trial at Bristol Crown Court, 15 defendants were given jail terms adding up to more than 120 years

- It was named after Sgt Julie Taylor, one of the undercover police officers involved

- Immortalised in The Clash’s song Julie’s Been Working for the Drug Squad

Many of the gang were also heavy drinkers and he had to keep up.

“I was drinking for England. It was a minimum of five or six pints a day and three or four shots. On a heavy day it would be 12 to 15 pints and who knows how much whisky.

His book, Undercover Operation Julie – The Inside Story, documents everyday life as he won the confidence of the gang members.

The pair set out to build trust and socialise with key members of the hippy community – offering their services clearing trees (Eric Wright could use a chainsaw) or helpfully putting their van to use offering to move people’s furniture.

On one comic occasion an upright piano went hurtling out the back of a van while the gang attempted furniture removal after a drinking and cannabis-smoking session.

With the local police unaware of the operation, on another occasion he enhanced his deep cover by directing drunken abuse against a village constable.

The truncheon-wielding PC chased the hippies from the pub, although as Mr Bentley recalls, the officer’s “athleticism had long gone” so they were able to out run him.

By then, Mr Bentley was so assimilated into the group that they gave him the nickname “cop killer” – because of his abuse of the officer.

One key gang member he built a “perfect” relationship with was Smiles. But this friendship almost undermined the whole operation.

“Really, when I look back, I wonder how I kept it together,” he says. “There was one occasion that stands out.

Image copyright Stephen Bentley

Image copyright Stephen Bentley “I was sat cross-legged with Smiles in his living room. Through smoking cannabis and drinking I came very, very close to losing self-control and confiding in him who I was, mainly because I really liked him. It was just sheer willpower that stopped me.”

During his undercover assignment, Mr Bentley continued to get on well with Smiles. He said: “I was relieved not to be involved in his arrest, but I went to see him in the police cells at Swindon.

“I’d shaved off the beard. When he recognised me he just said ‘No hard feelings’. I felt very emotional. Close to tears. He felt like a brother.”

In February 1977, with evidence against the gang already gathered, the undercover pair were pulled out.

Raids on 87 addresses in Wales, London, Cambridge and France between March and December 1977 would eventually turn up laboratory equipment, more than 1m in cash and shares, and enough LSD for 6.5 million doses.

Although he won a promotion, Mr Bentley became alcohol-dependent, continued to take cannabis and his second marriage broke down.

It is something he largely blames on his undercover work.

“I was treated so badly, that it still rankles now,” he says. “I was a good copper and enjoyed the camaraderie of being part of a crack detective team. I loved the job and resigned while suffering from severe depression.

“My drug habits would never have happened without my exposure on Op Julie.”

Image copyright PA

Image copyright PA While Operation Julie was deemed a success – a total of 120 arrests were made, resulting in 15 convictions and prison sentences totalling more than 120 years – Mr Bentley thinks the long term impact was “negligible”.

He believes it was a missed opportunity to develop specialist undercover police work.

“The surveillance and undercover techniques honed during the operation were lost,” said Mr Bentley. “Infiltration is highly specialised and should have become a career option to avoid the transition back to normal policing.

“Op Julie was special because it surmounted this parochialism and proved what could be achieved by a de facto national squad.

“The establishment didn’t want to know.”

He maintained a national squad of undercover specialists could have helped beat the influx of cheap heroin into the UK during the 1980s.

He also believes the reputation of undercover policing has been ruined by the Metropolitan Police which targeted protest groups, left wing MPs and family justice campaigners in an era that is now subject to the Pitchford inquiry.

Mr Bentley branded tactics used by Met Police undercover officers, including Mark Kennedy – who had a four-year relationship with an environmental campaigner – as “absolutely disgusting”.

“I don’t even agree with infiltrating protest groups,” he says. “I don’t think the police have a right to get involved unless they’re causing serious damage, or letting off bombs.

“In those days the big problem was drugs but if we had set up a national squad then it could have been the forerunner of one capable of tackling organised crime and terrorism.

“We still have a massive problem with that, and it is international, not just in the UK and the USA. I’d still advocate for the setting-up of a national squad now.”

Read more: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-hampshire-37439797