Margaret Atwood: All dystopias are telling you is to make sure youve got a lot of canned goods and a gun

As her reimagined version of Shakespeares Tempest is released, the acclaimed author of The Handmaids Tale and Maddaddam talks about how the world of 2016 is starting to look alarmingly like something from one of her books

On Thursday, just as Iamsaying goodbye to Margaret Atwood at the end of our interview, Iget a text message. Oh, I say. Bob Dylans won the Nobel prize. She is about to have herphotograph taken, and is arranging arakish grey felt hat atop her steely curls. She looks at me, opens her mouthvery slightly, and widens her eyes. They are the faintly unrealistic blue of a Patagonian glacier.

For what? she says, aspirating the word what with devastating effect.

If Atwood herself occasionally checks her phone for missed calls from Stockholm on such mornings, she does not admit to it; in any case, fellow Canadian Alice Munros victory in 2013, commemorated with a generous tribute by Atwood in this paper, will have queered that particular pitch for some years to come.

We are speaking at the British Library, where, later that day, the 76-year-old author will receive a different award: the English PEN Pinter prize. She will also bestow one, too, on Ahmedur Rashid Chowdhury, the Bangladeshi publisher of remarkable courage known as Tutul, who last year survived, in his Dhaka office, a machete-and-gun attack by Islamic extremists. At least nine Bangladeshi activists, writers and intellectuals have been murdered since the beginning of last year.

Atwoods PEN Pinter prize lecture, titled An Improvisation on the Theme ofRights, which she also delivered on Thursday, ends with a reflection on the dystopias of her fiction: that of The Handmaids Tale (1985) and of her recent MaddAddam trilogy. The first describes an America transformed into atheocracy that treats women as mere childbearing chattels after a state of emergency is declared following an assassination. (They blamed it on the Islamic fanatics at the time, the novels narrator explains.) The second deals with a world in which the planets resources are severely depleted. A situation, she explained in the lecture, that leads to civil chaos. Then warlords and demagogues take over, some people forget that all people are people, enemies are created, vilified and dehumanised, minorities are persecuted, and human rights as such are shoved to the wall. Not so much a distant and frightening future, she said, as the cusp of where we are living right now.

Readers of The Handmaids Tale haveindeed found elements of its story looming alarmingly close in recent weeks. See Donald Trumps remarks about women; see the virulently anti-choice Republican vice-presidential candidate Mike Pence. See, even, Trumps Republican detractors, such as Mitt Romney, decrying hisremarks on groping because they demean our wives and daughters. Arewe in Gilead the America of The Handmaids Tale? Close, yes. For sure. And everything in it, she says, was based on things that had actually happened. Including everyone tugging on a rope during hangings so that no one is guilty: thats from English history, she says. Ceauescu in Romania forcing women to have children quotas for childbirth. The fact that, in the United States, teaching a slave to read was against the law. And then sumptuary laws who can wear what. Who can cover up what, who has to, and can, cover up what part of which bodies thats been a part of human culture for avery long time.

She mentions an article that famously accurate US psephologist Nate Silver published on his website, fivethirtyeight.com. (His one famous failure was in notpredicting Trumps victory in the Republican primaries.) Silvers article includes a pair of maps. One shows howthe US would look if only men voted: almost entirely red. The other shows how the US would look if only women voted: almost entirely blue. It spawned a hashtag, says Atwood (who is a frequent poster on Twitter) called #Repealthe19th. The 19th Amendment is what gave women the vote. So there are Trump supporters who want to takethe vote away from women. The Handmaids Tale, unfolding in front of your very eyes. (In fact, the Washington Post pointed out that #Repealthe19th spiked as a social media topic not only through the enthusiasm of Trump supporters, but through its being heartily condemned by his detractors; but still, there it was as a notion, red and bleeding and out there.)

Her whistlestop tour through feminism goes like this: First wave, the vote. Second wave, the image. Now its about violence and rape and death: weve got down to the nitty-gritty. Earlier this month, when she spoke atthe Southbank literature festival in London, she talked about the most amazingly vicious online abuse of women. Whatcentury are we in? sheasked. Apparently, the 12th.

When The Handmaids Tale was published, she says, the novel was reviewed by British critics as an enjoyable fantasy, and by the Canadians with a certain anxiety (Could it happen here?). In America, though, there was a sense of: How long have we got? She sighs. Apparently, not as long as I thought With any cultural change there is a push and a pushback. Trump has brought out a huge pushback that was originally against immigrants. Now it has shifted to being very misogynistic, partly because of Hillary Clinton. You have not seen anything like this since the 17th-century witchhunts, quite frankly.

Can you understand the appeal ofTrump, I ask? He brings out the temper-tantrum-throwing wilful brat in all of us. Why cant I do what I want? Why cant I have what I want? Those other people are stopping me. Those other people have a bigger lollipop that I do, Im going to take their lollipop away from them. But on the other hand, he couples that with the most amazing whining. She mentions the complaint by Trump that his microphone malfunctioned during the first televised presidential debate. (Rubbish.)

I tell you this, she continues. Hillary Clinton is a better man than Trump. She has more connection to the traditional male virtues. She has comported herself in a much more manly fashion. Ask any real alpha males that youll know and theyll say of Trump, This is the guy wedidnt like at school because he was abully, but as soon as anyone pushed back at him he started to whine.

What does she think, then, of Clintons campaign? Well, its more of acampaign. Trump has taken about 10 different positions on everything, so there is no way of knowing what he really thinks. You actually just dont know. He will adopt a position depending on what reaction is mirrored back to him. Basically, its very close to being a manifestation of a mob: burn them at the stake, screaming and yelling.

Like the Salem witch trials, then? She proceeds to talk about them: Atwood likes to take a long historical sweep. Her heroes of this tragic episode, dramatised by Arthur Miller in The Crucible, are Rebecca Nurse, who refused to admit that she was a witch and declined to accuse others, meaning she was hanged; and Giles Corey, who refused to plead at his trial, meaning that he was pressed that is, crushed by heavy stones until his lungs collapsed and he died. By sacrificing himself thus, and not allowing his case to be tried, his family inherited his property, which otherwise would have been confiscated.

However, she says, after a fairly long disquisition on the legal history of 17th-century Massachusetts, this is not at all what the Trump situation is like. Salem was much more dignified Salem at least had rules for the trials. She hunts around for a better comparison. Its like Night of the Hunter, she says. Robert Mitchum. Directed by Charles Laughton. Just a great film. At the end they catch this guy whos been murdering women and has been trying to get hold of some children to kill them too. He is seen off by Lillian Gish playing an old lady in a rocking chair with a shotgun. (A sudden vision arrives, unbidden, of Atwood in arocking chair with a shotgun.) She peppers him with shot, he gets caught and put in jail and theres a mob outside who want to lynch him. So the very same Christian, righteous people who have played the virtuous townspeople are now screaming for his blood. This is what its like. Those mob scenes at Trump rallies: burn her, lock her up, killher. They think they are at the wrestling, but let those people out, andyou have a lynchmob.

We turn to the scenarios she sketched in the MaddAddam trilogy: a world of internet insecurity, pig-human hybrids, environmental devastation, oil fetishists and complete corporate takeover of states. Do dystopian novels, I wonder, actually do anything? Can they change behaviour? They are, she says, more like weathervanes than guides on averting disaster. All dystopian novels are telling you to do is make sure youve got a lot of canned goods and a gun. Do you have canned goods and a gun in Toronto? Im too freaking old. Im probably not going to make it through the zombie apocalypse anyway.

The literary news, as we speak, has been recently all about the unmasking by an Italian investigative journalist of the real identity of Elena Ferrante, the pseudonymous author of the hugely popular Neapolitan novels. She probably went too far in putting out a fake autobiography. Which is like an invitation: expose me, says Atwood. (She is referring to Frantumaglia, which is about to be published in English not an autobiography as such, but a collection of letters, essays, interviews and the like.) But shes not committed a crime. Nor do I feel that she was a bad person to write under a pseudonym. She did what she wanted to do. It worked spectacularly well, and then there are the books. People will read them a bit differently, thats inevitable. But it doesnt make them bad books.

Atwood herself published pseudonymously a bit, when she was young in the student magazine, to fill the pages. And she wrote a comic strip under another name in the 1970s. Then there was a skittish review of one of her own books she wrote once, under the not-very-veiled byline of Margarets Atwood, which referred to certain anagrammatic figures: ethnologist Gwaemot R Dratora, the architect Wode M Gratataro, and the profile-writer Greta Warmodota. Invisibility isnot her thing: especially when she, and Canadian fellow writers, worked sohard in the 1970s to improve their own visibility. I dont think Im entitled to whinge too much, because its my fault. I used to go on the Greyhound buswith copies of my books in a cardboard box, and give readings in school gymnasiums. Id sell my own books and collect the money, put it in a brown paper envelope and take it back to the publisher. She looks at me with wide eyes. What sort of a wimp are you? Have you never tramped through the snow with your books in a cardboard box on a sled?

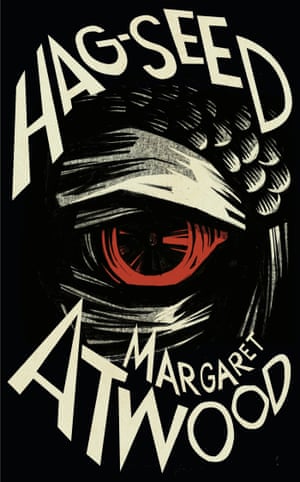

The latest book that she is, metaphorically at least, carrying around with her on a sled is neither dystopian nor utopian, but a story based on The Tempest, called Hag-Seed part of a series ofShakespearean reworkings commissioned from writers including Jeanette Winterson and Anne Tyler. In her deft story, Prospero is a director called Felix, deposed from his position as artistic director of an important theatre. Bent on revenge, he stages a version of TheTempest in a prison, and plots his payback. I worry, though, that Prospero is a part often taken on by actors reaching the end of their careers. I hope theres to be no talk of Atwoods abjuring magic, or any nonsense like that. No, she tells me. No need to fear. The last part actors usually take is Lear.That really makes people cry.

This is very Atwood: nearly everything she says is delivered precisely, and lightly iced with irony, whether shes being immensely warm, or plunging her dagger into some unfortunate victim.

Hag-Seed by Margaret Atwood is published by Penguin at 16.99. To order it for 11.99 go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p on online orders over 10. A 1.99 charge applies to telephone orders.

Read more: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/oct/15/margaret-atwood-interview-english-pen-pinter-prize