Man’s death hints at wretched medical care in private immigration prisons

Jose Jaramillo suffered a catastrophic illness due to inadequate care at Cibola County correctional center. The justice department had ended its contract with the facility but in a stunning reversal another agency has reopened it

Theodula Jaramillo had kept vigil over her sons deteriorating body for seven years before he died on Independence Day.

On some days, when there were no available chairs at the Sagecrest Nursing Center in Las Cruces, New Mexico, the 79-year-old would stand for eight hours at a time, watching his motionless body for signs of pain or discomfort. Only his eyes and, on occasion, his mouth were left with any movement.

Although it was a kidney infection that finally took his life three months ago, Theodula had no doubt who was to blame: It was the prison, she said in Spanish, her voice quivering. Theyre who triggered everything. All of this suffering could have been been prevented just by giving him simple medicine.

Jose Jaramillo was 52 years old and in the middle of a three-year sentence when he collapsed inside his cell at the Cibola County correctional center in May 2008. His crime had been to illegally enter the US to reunite with his wife and children. Jaramillo would never regain adequate cerebral functions, as his impoverished family battled on his behalf, first to keep him in America and then to sue the prisons private contractor, Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), for medical negligence.

The father of three, who had lived almost his entire life in the US, had been detained in one of the federal governments secretive criminal alien requirement prisons, a network of 13 privately operated facilities dotted mostly around the American south, which almost exclusively detain low-risk inmates convicted of immigration offenses.

Just weeks after Jaramillos death this year, the US Department of Justice announced that all 13 of these private prisons would be closed following a scathing audit that revealed they were markedly less safe than similar facilities run directly by the government. The first scheduled to close would be the one where Jaramillo suffered his catastrophic illness, as reports indicated that the Cibola County prison was among the worst providers of medical care in this cohort of private prisons, and the DoJ found that medical complaints were the most frequent grievance of inmates held in the contract network.

But just as migrant rights advocates celebrated the planned closure, it was announced last week that the Cibola County facility would in fact remain open, as CCA secured a new contract with a different arm of the federal government, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Ice), to turn the prison into an immigration detention center.

The failings in Jaramillos case, reported here for the first time and pieced together through court documents, depositions, public records and interviews, reveals extraordinary details of the substandard medical care given to inmates in this facility and, advocates warn, the likelihood of continued failure when the institution reopens its doors to detainees this week.

But Theodula Jaramillo knew nothing of the DoJ announcement, and took no solace when she was told. She stared at the floor in her small bungalow in the village of Hatch, where mold creeped up the woodchip walls and seams on the ceiling drooped from their fixings. It makes no difference to us. It wont bring him back, she said. Everyone involved should pay for what they did to him.

Two layers of fencing and thick rolls of razor wire separated the remaining inmates from the Zuni mountain range, which undulated in the distance behind the Cibola County correctional centers recreation ground. The facility once held about 1,200 inmates but just a few hundred remained when the Guardian visited the grounds to photograph the prison in the last week of September. The prison is nestled in a corner of the tiny village of Milan, a former mining town with just 1,300 residents about an hour and halfs drive from Albuquerque.

Prisoners could be seen in small groups jogging and exercising next to the perimeter fence, dwarfed by the empty grounds. Within a minute, a patrol car sped along the outside road and pulled up next to the north-western guard tower.

You cant take pictures here, a guard shouted. You need to leave. Now.

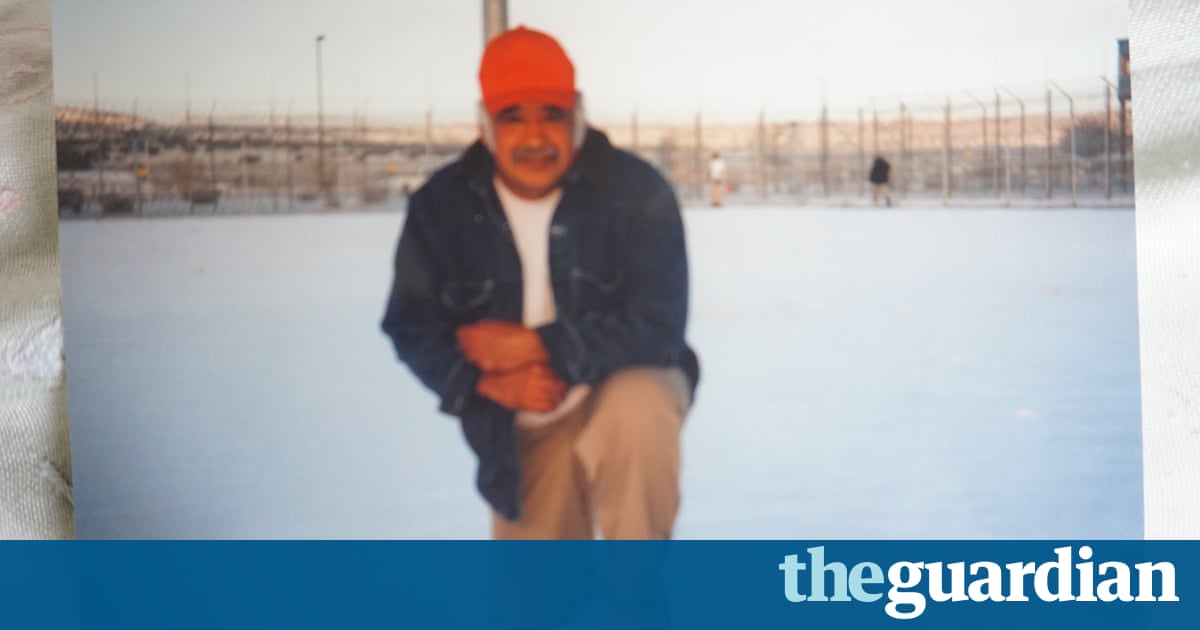

The Jaramillo family have scant memories of Joses time inside. They were never able to visit him and he rarely shared his experiences of incarceration with them. Occasionally he would send photographs in the mail taken with a smuggled camera. One, dated February 2008, shows him crouched in snow in the prisons recreation ground, smiling at dusk.

That year, an annual audit by the Federal Bureau of Prisons had found serious failings in the standard of medical care that CCA offered to inmates, noting: Needle/syringe inventories were not accurate. Chronic care clinics physical examinations were incomplete or not performed. Annual foot exams were not current Nursing care was not always in accordance with protocols and the State Nurse Practices Act.

The prison was also without a physician on staff for several periods of that year against the parameters of its contract with the government, while staff repeatedly reported serious delays in obtaining basic medication from approved suppliers, according to deposition testimony from multiple CCA employees.

Nonetheless, the federal government still paid the company an annual bonus added to its three-year, $237m baseline fee meaning CCA was paid well in excess of $82,000 per inmate, per year.

In that particular facility in a remote area of New Mexico, it was always difficult to maintain the staffing, conceded former Cibola County prison warden Walt Wells during a deposition hearing in 2013. But we got the job done.

Lawyers disagreed with Wellss positive assessment, and argued it was this chronic understaffing and the poorly resourced clinic that ultimately led to Jaramillos catastrophic illness.

The 52-year-old, a barrel-chested man who spent most of his life labouring, was diagnosed with diabetes by prison medical staff in 2007. Bureau of Prisons infectious diseases regulations to which, lawyers argued, CCA was bound by contract dictated he should have received a routine pneumococcal vaccine soon after diagnosis; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends all diabetics receive the vaccine due to their substantially higher risk of pneumonia and meningitis. But no such vaccination was provided, and Jaramillo went unprotected from pneumonia and meningitis for the rest of his time inside.

You have 1,000 men, living together in bunk beds. They have 2ft apart from one another, and so bacteria is everywhere, said Lisa Curtis, a veteran medical malpractice attorney in Albuquerque, who took Jaramillos case to federal civil court. For a diabetic without a vaccination, that is a death sentence.

During the case CCA officials argued, however, that these Bureau of Prisons rules did not apply to their facilities, which, they argued, were governed by company rules.

CCA, which this week rebranded itself as CoreCivic, did not answer a detailed list of questions related to Jaramillos case, staffing issues at the facility and contractual obligations, citing healthcare privacy considerations.

But CoreCivic spokesman Jonathan Burns said: Protecting the health and safety of those entrusted to our care is our top priority.

Curtis, who described the case as one of the clearest violations of basic medical care she had ever encountered, said she believed the subtext was clear: They just believed pneumococcal vaccinations were too expensive. The CDC lists the current price of a pneumococcal vaccination kit, which contains 10 doses, at $86.71 or $8.67 each.

Medical experts who testified on behalf of the Jaramillo family argued the vaccination itself would probably have prevented what happened next.

The symptoms began in the first week of May. Pains in his throat. Earache. Body ache. Fever, coughing and nausea. He lined up for the prisons sick call, which opened for just 45 minutes at 5am, allowing prisoners a short window to sign requests for medical assistance. Staffed by just one nurse, according to deposition testimony, the queues were so long many inmates gave up before receiving any attention. Between three to five nurses worked in the prison on each shift. Nurses estimated that they would see 400-500 patients a month.

Medical records and depositions show that Jaramillo was seen first on 8 May and then again on 11 May, and finally on the morning of 22 May. He told his family his symptoms were getting worse, that he was in pain and wanted to go to the hospital, but records show he was only ever given cough syrup and saltwater by medical staff.

They didnt listen to him for weeks. He should have gone to hospital, but they just waited so long, said Jaramillos 20-year-old daughter, Judy, who spoke to her father on the phone during this period.

Under CCA policy any inmate who reported sick three times with the same symptoms should automatically have been referred to a physician with the ability to prescribe medicine. But the referral never happened, according to the deposition of a nurse who saw Jaramillo at his last sick call.

Instead, just hours after he was examined on 22 May, Jaramillo was found collapsed in his cell. He was placed in a wheelchair and taken back to the clinic where the nurse described him now as just flaccid, loosely able to articulate intense pains in his chest. The prison finally called emergency services.

The undiagnosed infection had turned to sepsis and then to pneumococcal meningitis.

Although years later CCA began administering the pneumococcal vaccine to inmates at the Cibola County facility, the chronic staffing issues remained. During a 2012 deposition hearing, the prisons long-serving nurse practitioner, June Kershner, told Curtis that once again the prison had no physician on staff, leaving the facility dangerously under-resourced. Inmates and staff now referred to her as doctor despite her lack of qualifications, and medication was prescribed by an Arizona-based doctor over the telephone.

An investigation by the Nation magazine found that the Cibola County facility accumulated more repeat deficiencies or significant flaws in health provision than any other private federal prison, with 30 out of 34 contract citations since 2007 related to poor standards of medical care. The investigation also identified three deaths, not including Jaramillos, linked to questionable care at the facility by the end of 2015.

These failures, argued experts, made Ices decision to keep the facility open all the more extraordinary, particularly when the Department of Homeland Security is conducting its own review of its use of privatised institutions, following the DoJ announcement in August.

Its just stunning that Ice is turning around and signing a new contract there, said Carl Takei, a staff attorney at the ACLUs national prison project. We have serious concerns about the medical care for Ice detainees being just as terrible as it was for BOP prisoners. Theres no reason to believe it will improve. Its the same company and the same facility.

On Monday, CCA chief executives formally announced the five-year contract with Ice, arguing: CCA already has an experienced, well-trained workforce at the Cibola County corrections center which, for many years, has provided an exceptional level of service to the BOP, and we are proud to have the opportunity to extend the same level of exceptional service to another federal customer under this new contract.

The village of Milan, with a population of just 1,300, was caught off guard when the DoJ announced the closure earlier in the summer. CCA is the largest employer here, and also in the neighboring town of Grants, where the company operates a controversial womens prison under a contract with the state government.

There were 245 jobs scheduled to be lost by the time the Cibola County prison was due to close, at the end of October. The village stood to lose a projected $358,000 in revenue from property taxes and gross receipts, while the county government would have lost $700,000 annually in taxes.

Families had already begun packing up and leaving town in September, as local government officials frantically pushed for solutions and endorsed CCA efforts to keep the prison open as it sought contracts with Ice, the US marshal service and the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

It will turn this community into a ghost town, said Marcella Sandoval, the Milan village manager in September. The prison is a lifeline for us.

Milan and Grants lost three-quarters of their population in the late 1990s after uranium mining in the regions rich mineral belt ceased. It was around this time that CCA bought facilities in the area, offering a chance of employment to those who remained in town.

The prison drew almost instant controversy. In 2001, inmates rioted over the quality of food, drawing local police and outside law enforcement who used teargas to quell the unrest. But residents soon grew used to the prisons presence. Many who spoke to the Guardian in September felt slighted by the federal governments decision to close the prison. In this heavily Democratic county, some said the decision had been enough to make them vote Republican at the election in November. Sandoval said the county was given no advanced warning and no assistance was offered to the local economy.

Milans police chief, Jerry Stephens, who commands the villages seven-strong police department, said just two escapes had occurred from the prison during his tenure as chief.

I dont think the community here worries about it at all, he said. A records request indicated his department had attended 49 assault calls at the prison between 2014 and 2015.

Despite this, the Department of Justices inspector general found that inmates in its contract prisons were nine times more likely to be placed on lockdown than in other comparable facilities, and assault rates were 28% higher than in federal prisons.

In an interview in October, Sandoval told the Guardian that the reopened facility could now eventually hold 1,400 detainees expanding its already stretched capacity by 200 beds. The decision basically saved us. Theyre rehiring and will have even more jobs this time, she said, relieved.

Jose Jaramillo wrote a short statement after he was arrested for illegal re-entry in August 2006: I know what I did is against the law and so I accept full responsibility for my conduct. I came back to work and be with my family.

Jaramillo had been pulled over as he drove from the chilli fields outside of Roswell, where he had worked backbreaking shifts for most of his life, starting at 5am and finishing at sunset. A sheriffs deputy had noticed he had a broken headlight, and later reported him to border patrol agents in New Mexico after he failed to present identification papers. Instead of running away when agents called to inform him he was likely to be arrested, he waited for them to arrive at the door that evening.

I think that just shows you what sort of a law-abiding guy he was, Lisa Curtis said.

That year over 29,000 people were convicted for illegal entry and re-entry. By 2013, that number had soared to just under 88,000 meaning more than half of all federal criminal prosecutions that year were for unlawful border crossings. By the time the DoJ announced it was abandoning all contracts with these 13 private immigrant jails, their populations had swelled to 22,000 inmates, costing the federal government $600m a year.

After he stabilized in 2009, Jaramillo was moved to the nursing home in Las Cruces. The federal government had initially moved to deport him, but the family successfully appealed after arguing he would die within days if he was moved back to Mexico. But the brain damage was irreparable. He had no movement from the neck down. When he spoke it was often nonsensical. On rare occasions when he could muster a coherent sentence, he told his daughter Judy, born in the US with full citizenship, that he wanted her to finish high school and become a nurse.

It was his dream, she said.

Judy is now training to become an elementary school teacher, but visited her father twice a week at the nursing home until his death in July. The family, who settled with CCA in 2014 for an undisclosed amount with no admission of liability, placed the money in a trust to pay for Jaramillos care, but knew the end was coming as his health rapidly deteriorated from another infection.

I just felt like the world was hitting me, Judy said of the day her father died. It was sadness and anger. Anger at the prison.