“Bullseye!” he shouts.

It isn’t quite a direct hit, but this journalist and famed mafia hunter doesn’t easily give up.

Maniaci has also felt the wrath of Vitale.

“His son tried to kill me,” he says.

“Bullet proof glass,” he says, tapping on the shop’s front window. “Look at these … they’re five centimeters thick, and I paid for them just for Pino.”

As Maniaci knocks back an espresso and lights up another smoke, I ask Francesco why he’s done this.

“Because he is Sicily. Simple,” he says. “He is all of us.”

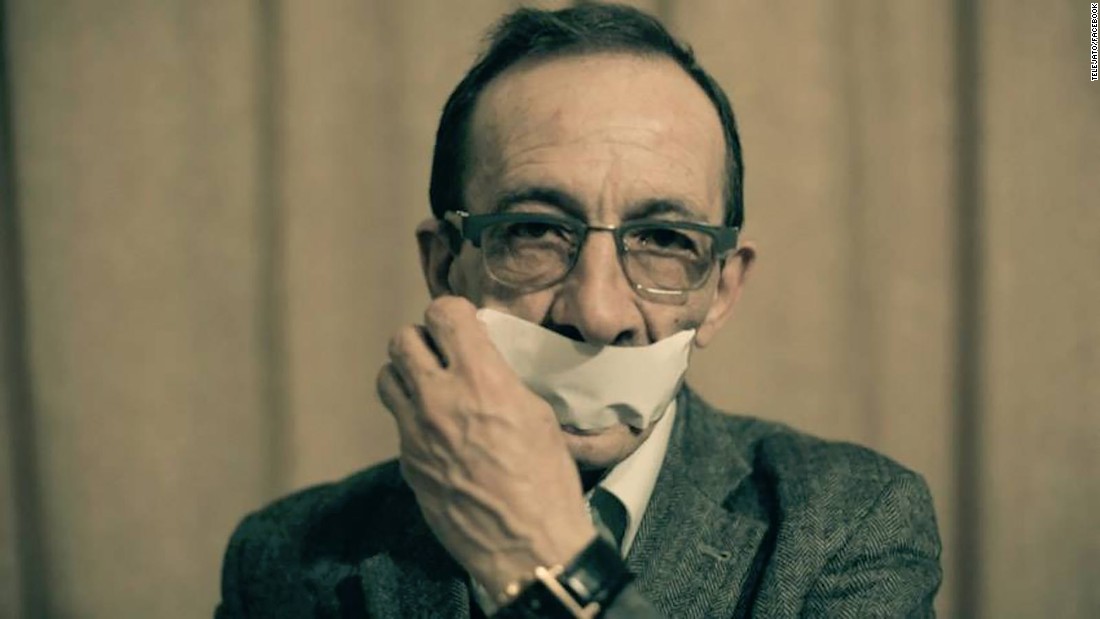

In a place where keeping quiet has long been the key to survival, Telejato has given voice to a generation of Sicilians beaten into submission by gangs.

In 2007, the network’s investigations uncovered a number of barns, owned by mafia families, operating illegally for more than 20 years. These were built on land belonging to others and stood as a symbol of the Cosa Nostra’s grip on power. Not only did they house animals, but they were said to be the headquarters for mafia summits and nicknamed the “Stables of Shame.”

Maniaci’s relentless reporting eventually sparked a major police probe which led to the barns being torn down.

He’s also scooped Italy’s biggest television networks time and again as the only journalist to witness the arrests of mafia bosses. In 2009, Maniaci’s cameras captured the celebrations on the streets as police nabbed Domenico Raccuglia. While spending 15 years in hiding, he was convicted in absentia for murder.

The arrest of Domenico Raccuglia

“Police tipped us off to his arrest and the arrest of many other Mafioso,” he says.

If there’s one thing the mafia truly hates, its bad publicity. You go after the mafia, and it comes after you.

The Cosa Nostra is believed to havemurdered at least six prominent journalists over the past several decades, and a Parliamentary report found Italian reporters were victims of more than 2,000 “acts of hostility” between 2006 and 2014. These include the torching of their cars and verbal and physical threats. No wonder so many Sicilians feel it’s best not to speak of the mafia at all.

In 2008, the Cosa Nostra wanted to teach Maniaci a lesson.

The son of Vito Vitale, the ruthless mob boss who murdered an informant’s young son and dumped his body in acid, was told to hunt the reporter down.

“I was going back to my car — it was night — and I see another car stop near me,” Maniaci says. “Two guys get out and block my door just as I try to shut it”.

Vitale’s son Michele grabbed onto his tie, yanking violently.

“He wanted to strangle me,” Maniaci says.

But as he began gasping for air — a jarring halt.

And another, and another.

The tie Maniaci wore on air that day was stuck.

“The double knot saved my life,” he says between drags of his cigarette.

As if this case didn’t have enough twists, Maniaci is launching legal action against the military police. His core claim: The hidden camera footage was tampered with to make him look guilty, because he doesn’t deny taking the money.

“The Mayor’s wife was advertising her shop on Telejato and Pino was picking up the money”, Ingroia says.

“300 euro plus 100 from the month before, and 66 euros in VAT tax. Who extorts for 400 euros and charges tax on it!?”

Ingroia claims Maniaci’s meeting with the mayor lasted about an hour, but was selectively picked apart, professionally edited down to a one-minute clip and then handed out to journalists complete with a press pack.

He’s also suspicious of Mayor De Luca.

“You can see him looking at this hidden camera when he hands the money over, making sure it’s visible. We suspect he was in agreement with police to trap Pino,” Ingroia says.

The burning question here is why? Why would the police or government allegedly go to such efforts to discredit a journalist?

Maniaci says they’re seeking revenge. “We managed to expose officials for mismanaging property seized from the mafia, worth billions of dollars,” he says.

Again, it’s hard to tell if Telejato’s reporting single-handedly sparked the corruption probe, but the scale of it is enormous. The reports focused on Silvana Saguto, a court official responsible for deciding who should take over companies seized by mafia. Saguto, who denies wrongdoing, is accused of taking bribes and parachuting friends and family into cushy, high-paying jobs at these ex-mafia businesses. She is one of 20 people charged.

There is one certainty in all this — it will be a very long time before anyone has any real answers. The only thing more notorious than the mafia is Sicily’s bureaucracy. Maniaci’s legal team admits the case could drag on for a decade. Prosecutors ignored repeated requests to clarify this and refused to answer questions about the case.

It also promises to be a painstaking wait for Telejato’s loyal viewers. When will they know if their anti-mafia hero is innocent or guilty? A target or a turncoat?

On with the show — and the probes

You can tell it’s almost show time.

Reporters suck down cigarettes and clatter away at keyboards in a tiny newsroom no bigger than your average living room. The noise crescendos with a boom from across the room.

“LETIZIA!” Maniaci snaps.

With my very average Italian, I put two and two together and figure he’s asking his reporter Letizia whether her story will be ready.

Letizia is Maniaci’s daughter and a highly regarded journalist; many of the awards crammed onto the newsroom shelves are for her fearless reporting.

Behind the scenes during showtime at Telejato’s studio

But there’s more to Telejato than just naming and shaming. Beyond exposing corruption, the network has led a tireless crusade against protection money.

Its persistent campaign has achieved incredible results across Sicily; and while the irony isn’t lost on me that it’s led by a man who himself is accused of extortion, the impact can’t be ignored.

Protection money, or “pizzo,” is big business for the mafia;

it’s estimated eight out of ten businesses still pay a cut, and while the amount depends on the industry,

it earns gangs tens of millions of dollars in Palermo alone. To speak about it is considered a dangerous social faux pas, but almost daily, Maniaci and his team plead with viewers to stop paying, to say “addiopizzo” or “goodbye extortion”.

“We’ve formed an association with local companies who want to say no. No to protection money, no to extortion. They have strength in numbers,” Maniaci says.

The group, LiberJato, was born out of a meeting between the reporter and longtime Telejato viewer Francesco Billeci, a local businessman sick of the mob’s financial stranglehold. Dozens of entrepreneurs have signed up, particularly those in the construction industry, where mafia protection rackets expect a cut of about 3%.

Maniaci believes persistence will pay off. He quotes a famous Sicilian novelist: “Leonardo Sciacia said 30 years ago, ‘this city is irredeemable’. I do not believe this.”

There’s no denying Maniaci’s resolve to clean up the “cancer” gripping his land, fending off threats against his life and the lives of his staff. But he is also an enigma and it’s hard to ignore the sinister side of the Maniaci life story. While he claims vendetta in his extortion case, Reporters Without Borders has stripped him, at least temporarily, of his prestigious title as one of the world’s 100 “Information Heroes.”

Enough of that. Maniaci tells me it’s time to work. Butting out his cigarette, he heads to the bathroom, adjusts his tie and combs the moustache as famous in Partinico as the man himself.

Today’s jam-packed rundown has a familiar theme — magistrates, government officials and corruption. Sore points for this old-school reporter.

It’s hard to comprehend: an anti-mafia hero, now accused of mafia-style antics, yet still protesting against them.

The old Sicilian saying “trust no one” is starting to ring true. It’s hard to know who to believe.