Great-grandson of man killed in Stalin’s purges to sue Russian state

Descendant given document revealing chain of responsibility for death, from Soviet leader to three executioners

A young designer in Russia plans to sue the state in an unprecedented case after an archivist sent him evidence appearing to name the agents of Joseph Stalins secret police who executed his great-grandfather.

Denis Karagodin, 34, received the document in the post after repeated requests to the Federal Security Service (FSB) for information about the circumstances of his great-grandfathers execution.

The typewritten paper appears to be a report in which three secret security officers confirm to a court that they have carried out the courts death sentence in the city of Tomsk. The stamped document featured the names and scrawled signatures of the three secret police agents who took responsibility for shooting Stepan Karagodin.

The dead mans great-grandson believes it is the first time that names of actual perpetrators of Stalins crimes have been directly associated with the deaths of their victims, and described it as a stunning discovery.

Karagodin does not know why the document was not stamped secret. He claims he can now establish a direct chain of responsibility from Stalin, to the secret police head, Nikolai Yezhov, to the local security officials in Tomsk, to the members of the tribunal who rubber-stamped the verdict, to the three executioners who pulled the trigger and, presumably, dumped Stepan Karagodins body into a mass grave on the edge of the city.

The historians and specialists I have spoken with cannot believe that I managed this, he said. Some of them were simply in shock that such documents even exist and that you can access them.

Karagodin, who lives in the same city where the execution took place, had been searching for years to find out what happened to his great-grandfather and to learn the names of the people who murdered him, but said in June that the state security services are doing everything they can to make this impossible.

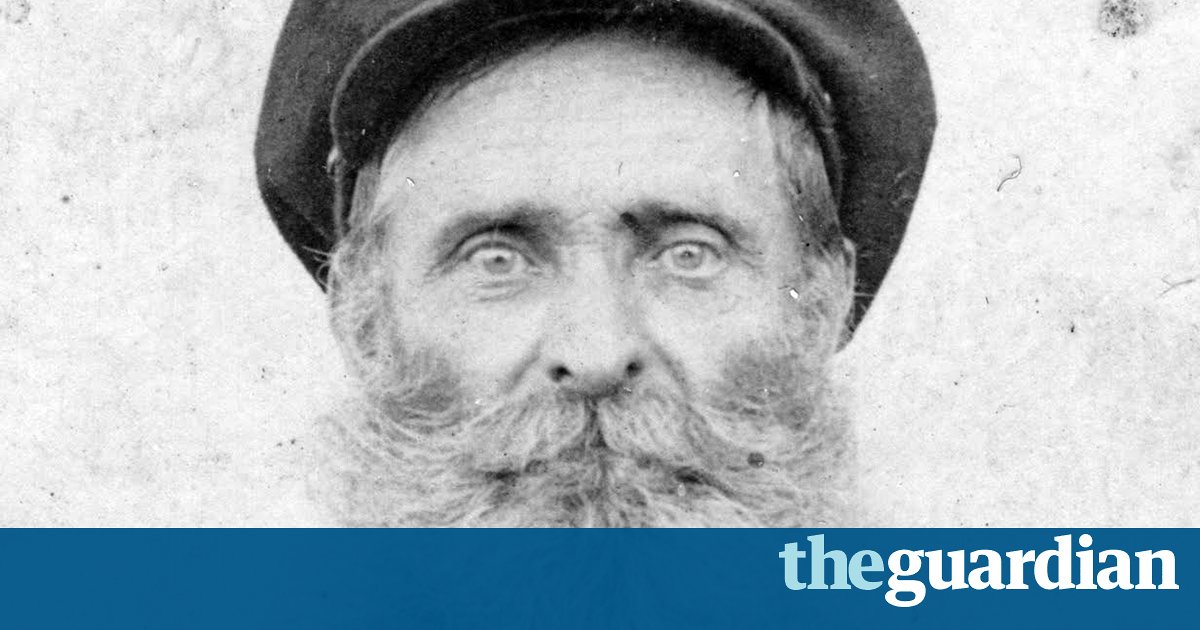

He began work in 2012, creating a website on which he collected every document he could find about the case. The result is a detailed account of the fate of Stepan, a Cossack farmer and father of nine who was executed in 1938 after being accused of working as a Japanese spy.

Karagodin believes his work is producing a much-needed discussion in a society that has long downplayed the communist states crimes against its own people and has done little to hold perpetrators to account.

Days after he published the names of the secret police agents, Karagodin received a letter from a woman he publicly identifies only as Yulya, the grand-daughter of one of the agents who signed the document.

Although confronting the truth about her own family was heartrending, Yulya thanked Karagodin for bringing out the entire truth of the countrys past.

Karagodin wrote back to her, saying he was sincerely grateful for her brave letter.

In addition, Karagodin has received dozens of letters from people thanking him for his work or seeking advice on how they can find out more about the deaths of their own relatives.

I give them advice, but it is really hard for me, Karagodin said. It is really hard. Each story is a particular hell and you have to delve into it and talk about these events without, at the same time, escaping from the particular hell of the Russian bureaucracy.

Slowly, a public conversation about historical crimes is emerging. In October, blogger Vladimir Yakovlev wrote a heartfelt post about his grandfather, whom he described as a murderer, a bloody executioner among whose many victims were even some of his own relatives.

My happiest childhood memories are connected with a spacious old apartment on Novokuznetskaya Street [in Moscow] that our family was very proud of, he wrote. That apartment, as I learned later, was not purchased or built, but confiscated. It was taken by force from a merchant family.

The couch on which I listened to fairytales and the armchairs and the buffet and all the other furniture in the apartment none of it was purchased by my grandfather and grandmother, he wrote. They just picked what they wanted from a special warehouse where the property taken from the apartments of executed Muscovites was stored.

Yakovlev also writes about the psychological wounds of Stalinism. When considering the scope of the tragedies of the Russian past, we usually count the dead, he wrote. But in order to assess the scope of the influence of these tragedies on the psyches of future generations, we need to count not the dead but the survivors. The dead died. But the survivors became our parents and the parents of our parents.

It took me years to understand the history of my family, he concludes. But now I have a better idea of the origins of my deep-seated, unmotivated fear. Or my exaggerated secretiveness. Or my absolute inability to trust and to form close relations. Or the constant feeling of guilt that has haunted me since childhood.

Coincidentally, the human rights group Memorial this month released an online database of 40,000 former Stalinist secret police agents. Russian media reported in November that the descendants of some of those named in the database have asked President Vladimir Putin to shut down the project out of fear they could become targets of revenge.

Karagodin now intends to seek to prosecute the entire criminal conspiracy that led to the death of his great-grandfather and the other six people named in the document.

When people tell him that the authorities would never allow such a case to go forward, Karagodin has a simple answer. Well try even if it is unsuccessful. At least it will go down in history as an attempt, he said.

A precedent can be a powerful thing.

A version of this article first appeared on RFE/RL