Defining justice: why it’s time to rethink our kneejerk response to crime

We are living in a country where the solution to just about any social problem is to create a law against it

Youve heard of distracted driving? It causes quite a few auto accidents and its illegal in a majority of states.

Well, this year, a brave New Jersey state senator, a Democrat, took on the pernicious problem of distracted walking. Faced with the fact that some people cant tear themselves away from their smartphones long enough to get across a street in safety, Pamela Lampitt of Camden, New Jersey, proposed a law making it a crime to cross a street while texting. Violators would face a fine, and repeat violators up to 15 days in jail.

Similar measures, says the Washington Post, have been proposed (though not passed) in Arkansas, Nevada and New York. This May, a bill on the subject made it out of committee in Hawaii.

Thats right. In several states around the country, one response to people being struck by cars in intersections is to consider pre-emptively sending some of those prospective accident victims to jail. This would be funny, if it werent emblematic of something larger. We are living in a country where the solution to just about any social problem is to create a law against it, and then punish those who break it.

Ive been teaching an ethics class at the University of San Francisco for years now, and at the start of every semester, I always ask my students this deceptively simple question: whats your definition of justice?

As you might expect in a classroom where half the students are young people of color, up to a third are first-generation college-goers, and maybe a sixth come from outside the United States, the answers vary. For some students, justice means standing up for the little guy. For many, it involves some combination of fairness and equality, which often means treating everyone exactly the same way, regardless of race, gender or anything else. Others display a more sophisticated understanding. An economics major writes, for instance,

People are born unequal in genetic potential, financial and environmental stability, racial prejudice, geographic conditions, and nearly every other facet of life imaginable. I believe that the aim of a just society is to enable its citizens to overcome or improve their inherited inequalities.

A Danish student compares his country with the one where hes studying:

The Danish welfare system is constructed in such a way that people pay more in taxes and the government plays a significant role in the country. We have free healthcare, education and financial aid to the less fortunate. Personally, I believe this is a just system where we take care of our own.

For a young Latino, justice has a cosmic dimension:

My sense of justice tends to revolve around my idea that the universe and life are so grand and inexplicable that everything you put into it comes back to you. This I can trace to my childhood, when my mother would tell me to do everything in life with love, faith, and courage. Ever since, I believe that any action or endeavor that is guided by these three qualities can be considered just.

Justice is punishment

The most common response to my question, however, brings us back to those street-crossing texters. For most of my students for most Americans, in fact justice means establishing the proper penalties for crimes committed. Justice, for me, says one, is defined by the punishment of wrongdoing. Students may add that justice must be impartial, but their primary focus is always on retribution. Justice, as another put it, is a rational judgment involving fairness in which the wrongdoer receives punishment deserving of his/her crime.

When I ask where their ideas about justice come from, they often mention the punishments (fair or otherwise) meted out by their families when they were children. These experiences, they say, shaped their adult desire to do the right thing so that they will not be punished, whether by the law or the universe. Religious upbringing plays a role as well. Some believe in heavenly rewards for good behavior, and especially in the righteousness of divine punishment, which they hope and generally expect to escape through good behavior.

Often, when citing the sources of their beliefs about justice, students point to police procedurals like the now elderly CSI and Law and Order franchises. These provide a sanitary model of justice, with generally tidy hour-long depictions of crime and punishment, of perps whose punishment is usually relatively swift and righteous.

Certainly, many of my students are aware that the US criminal justice system falls far short of impartiality and fairness. Strangely, however, they seldom mention that this country has 2.2 million people in prison or jail; or that it imprisons the largest proportion of people in the world; or that, with 4% of the global population, it holds 22% of the worlds prisoners; or that these prisoners are disproportionately brown and black. Their concern is less about those who are in prison and perhaps shouldnt be than about those who are not in prison and ought to be.

They are (not unreasonably) offended when rich or otherwise privileged people avoid punishment for crimes that would send others to jail. At the height of the Great Recession, their focus was on the Wall Street bankers who escaped prosecution for their part in inflating the housing bubble that brought the global economy to its knees. This fall, for several of them, Exhibit A when it comes to justice denied is the case of the former Stanford student Brock Turner, recently released after serving a mere three months for sexually assaulting an unconscious woman. They are (perhaps properly) outraged by what they perceive as a failure of justice in Turners case. But they are equally convinced of something I struggle with that a harsher sentence for Turner would have been a step in the direction of making his victim whole faster. They are far more convinced than I am that punishment is always the best way for a community to hold responsible those who violate its rules and values.

In this, they are in good company in the US.

There oughta be a law

Of course, the urge to extend punishment to every sort of socially disapproved behavior, including texting in a crosswalk, is hardly a new phenomenon. Since the founding of the United States, government at every level has tended to make unpopular behavior illegal. Just to name a few obvious examples of past prohibitions now likely to stop us in our tracks: at various times there have been laws against having sex outside marriage, distributing birth control, or marrying across races (as highlighted in the new movie Loving).

In 1919, for instance, a constitutional amendment was ratified outlawing the making, shipping or selling of alcohol (although it didnt last long). You might think that the experience of prohibition, including the rise of violent gangs feeding on the illegal liquor trade, would have given us a hint about the likely effects of outlawing other mind-bending substances, but no such luck.

One big difference between the 18th amendment and todays drug laws is that, although prohibition outlawed traffic in alcohol, it didnt mention consumption. No one got arrested for drinking. By comparison, as the Huffington Post reported last year:

Law enforcement officers made just over 700,000 arrests on marijuana-related charges in 2014 Of that total, 88.4% or about 619,800 arrests were made for marijuana possession alone, a rate of about one arrest every 51 seconds over the entire year.

One marijuana arrest every 51 seconds. It should be no surprise, then, that drug possession is a major reason why people end up in debt (from court-imposed fines), locked up, or both but hardly the only reason. Punishment is the response of choice for all kinds of behavior, including drinking in public (which is why people wrap their beer bottles in paper bags and kids who look up to them do the same with their soda cans), indecent exposure, lewd conduct, prostitution, gambling and all kinds of petty theft.

But doesnt punishing undesirable behavior have a deterrent effect, and doesnt more and harsher punishment increase that effect? This is obviously a hard thing to measure, but there is data available suggesting that lighter penalties for a particular crime do not necessarily result in more of that crime.

Take petty theft. Different states have different thresholds for what counts as petty and what is the more serious crime of grand larceny. Petty theft is usually classified as a misdemeanor, a category of crime that carries sentences of up to a year in a county jail. Above a certain dollar amount, thefts become felonies, which means those convicted serve at least a year and often many years in state prison. Depending on the state, some felons also lose their voting rights for life. Those convicted of federal felonies may not serve on juries, may not be able to work for the federal government, and are often not permitted to work for labor unions. A felony conviction is a big deal.

The Pew Charitable Trusts wondered what would happen if states treated fewer thefts as felonies by raising the dollar cutoff for a felony prosecution. Pew asked: Would there be more minor theft because the penalties were lower? (Some state felony thresholds were, in fact, shockingly low. Until 2001, in Oklahoma, stealing anything worth more than $50 would throw you into that category. Even that states new limit, $500, is still on the low side.)

The Pew researchers examined crime trends in 23 states that have raised the dollar threshold for felony theft and concluded that it had no impact on overall property crime or larceny rates. In fact, since 2007, property theft has been declining across the country, with no difference between states with higher and lower felony thresholds. So at least in the case of petty theft, threatening to send fewer people to state prison does not seem to raise the crime rate.

Whats the alternative?

In the late 1980s, the United Kingdoms first female prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, adopted the slogan there is no alternative, often shortened to Tina. In Thatchers case, she meant that there was no imaginable economic alternative to her campaign to destroy the power of unions, deregulate everything in sight, and gut the British welfare state. Its hard indeed to imagine other ways of organizing things when there is or at least is believed to be no alternative. Its hard to imagine a justice system that doesnt rely primarily on the threat of punishment when, for most Americans, no alternative is imaginable. But what if there were alternatives to keeping 2.2 million people in cages that didnt make the rest of us less safe, that might actually improve our lives?

Portugal has tried one such alternative. In 2001, as the Washington Post reported, that country decriminalized the use of all drugs and decided to treat drug addiction as a public health problem rather than a criminal matter. The results? Portugal now has close to the lowest rate of drug-induced deaths in Europe three overdose deaths a year per million people. By comparison, at 45 deaths per million population, the United Kingdoms rate is more than 14 times greater. In addition, HIV infections have declined in Portugal, unlike, for example, in the rural United States, where a heroin epidemic has the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention worried about the potential for soaring infection rates.

All right, but drug use has often been called a victimless crime. Maybe it doesnt make sense to lock up people who are really only hurting themselves.

What about crimes like theft or assault, where the victims are other people? Isnt punishment a social necessity then?

If youd asked me that question a few years ago, I would probably have agreed that there are no alternatives to prosecution and punishment in response to such crimes. That was before I met Rachel Herzing, a community organizer who worked for the national prison-abolition group Critical Resistance for 15 years. I invited her to my classes to listen to my students talk about crime, policing and punishment. She then asked them to imagine the impossible other methods besides locking people up that a community could use to restore itself to wholeness.

This is the approach taken by the international movement for restorative justice. The Washington DC-based Centre for Justice and Reconciliation describes it this way: Restorative justice repairs the harm caused by crime. When victims, offenders, and community members meet to decide how to do that, the results can be transformational.

Similarly, transitional justice is the name given to a range of measures taken in countries that have suffered national traumas, including ethnic cleansing and other extensive human rights violations. According to the International Center for Transitional Justice, such measures to heal a wounded country and deal with often terrible crimes do include criminal prosecutions, but the emphasis is often placed on truth commissions, reparations programs, and various kinds of institutional reforms, or even, as the Centre for Justice and Reconciliation suggests, meetings between victims, offenders, and other persons to emphasize accountability and make amends.

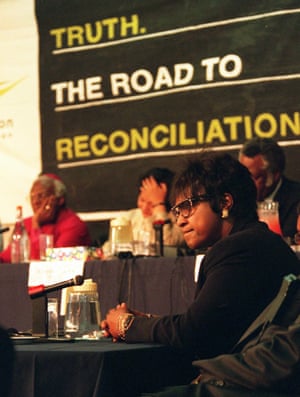

The most famous of such experiments has undoubtedly been South Africas Truth and Reconciliation Commission. From 1948 to 1994, South Africa operated under the official policy of apartheid, the legal separation of South Africans into four different racial categories with four different levels of rights. The South African government employed all the usual tools of state terrorism murder, torture, beatings, incarceration and daily repression to keep the oppressed majority out of power. Eventually, international sanctions and internal resistance, followed by an extraordinary negotiation between the African National Congress leader Nelson Mandela and the then president, FW De Klerk, brought a peaceful end to apartheid.

In 1994, after Mandela had become president and the crimes of that countrys white regime were at an end, that Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established to confront the countrys history of apartheid atrocities. Behind that process was a recognition that there could be no peaceable future without a public acknowledgment of the harm that had been done by those who had done it. In South Africa, even torturers and murderers under the apartheid system were granted amnesties for their crimes as part of a social healing process, but only after they had publicly admitted their actions and genuinely asked for forgiveness. It was not punishment but the acknowledgment of wrongdoing that marked the beginning of justice in that country, and it seemed to work for many of those who had suffered grievously under apartheid.

A similar approach might work in the United States. Indeed, it already happens all the time on a small scale around the country, through community mediation services. These organizations help neighbors settle disputes that might otherwise result in a trip to civil courts or the pressing of criminal charges. An important aspect of the process is listening to and acknowledging the harm others have experienced. It might be possible to expand this kind of mediation to address more serious instances of harm to individuals or a community, and to work out means of restitution that did not involve prison time.

There are other alternatives to punishment as well. For example, as Critical Resistance suggests, instead of training police forces to deal with people experiencing mental health breakdowns by arresting them and putting them in the justice system, we might begin to treat such events as what they are: health crises. Its a horror that jails and prisons have become the biggest mental hospitals in the country with the justice department reporting that half of those now incarcerated have some form of mental illness.

Some communities have also begun to question the wisdom of the broken windows approach to policing first proposed by the criminal justice scholar George Kelling and political scientist James Q Wilson. They argued that when the police enforced laws and informal rules against nuisance behavior in neighborhoods, reductions in more serious crimes followed.

In their seminal 1982 article on the subject in the Atlantic,Kelling and Wilson suggested that just as an untended building with one broken window was eventually likely to end up with all its windows broken, untended behavior also leads to the breakdown of community controls. They wrote approvingly of a police officer who made a habit of arresting for vagrancy anyone who broke the informal rules of the neighborhood to which he was assigned by begging for money at a bus stop or drinking alcohol from an unwrapped container or on the sidewalk of a major street.

Bill Bratton, New York Citys just-retired police commissioner, championed this broken windows approach to policing, including a race-based stop-and-frisk policy in which police searched New Yorkers on the streets of their city 5m times between 2002 and 2015. Nearly 90% of those stopped were, according to the New York Civil Liberties Union, completely innocent of anything and of the remaining 10%, only one-quarter, or 2.5% of all stops, resulted in convictions most often for marijuana possession. But hundreds of thousands of people, mostly young African American and Latino men, lived with the expectation that, at any time, the police might stop them on the street in a humiliating display of power. In a landmark 2013 decision, a New York federal court found the police departments stop-and-frisk policy unconstitutional.

Heres another idea: even people of goodwill who are not yet ready to jump on any prison abolition bandwagon might agree that we could stop sending people to jail for many misdemeanors.

In my state, California, there were 762,002 arrests for misdemeanors in 2014 alone. Of these, 92,469 were for drug possession, 1,265 for glue sniffing (a crime of the truly poor and desperate), and another 90,061 for being drunk in public. The largest single category, however, was driving under the influence, or DUI, with 151,416 arrests. Thats a total of almost 335,000 people arrested in one state in one year for crimes connected with the use of either legal or illegal drugs. Add to that the 58,569 people arrested for petty theft, imagine similar figures across the country, and you can see how the jails might begin to fill with record-setting numbers of prisoners.

Even when never convicted, those arrested often end up spending time in jail because they cant afford bail. And spending time in jail can cost you your job, your children, even your home. Thats a lot of punishment for someone who hasnt been convicted of a crime. In August 2016, the US justice department filed documents in federal court arguing that holding people in jail because they cant afford to bail themselves out is unconstitutional a major move toward real justice.

So the next time you find yourself thinking idly that there oughta be a law against not giving up your seat on a bus to someone who needs it more, or playing loud music in a public place, or panhandling stop for a moment and think again. Yes, such things can be unpleasant for other people, but maybe theres a just alternative to punishing those who do them.

Ill leave the last words to a student of mine, who wrote: My definition of justice is some sort of restitution and admission of wrongdoing from someone who wronged you in the past My family has influenced my definition of justice in teaching me that even if someone does something wrong there should always be room for forgiveness and, if they are sincere, forgive them and that is justice.

Now, its your turn to define the term and so our world.

Rebecca Gordon, a TomDispatch regular, teaches in the philosophy department at the University of San Francisco. She is the author of American Nuremberg: The US Officials Who Should Stand Trial for Post-9/11 War Crimes (Hot Books). Her previous books include Mainstreaming Torture: Ethical Approaches in the Post-9/11 United States and Letters from Nicaragua.

Read more: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/sep/27/us-justice-system-crime-punishment-prison