Anti-gentrification activists plaster ‘karmic infractions’ on Seattle shops

An unconventional protest by two artists is singling out businesses they say are destroying communities in a historically African American part of the city

On a corner of Seattles historically black Central Area, Sea Suds car wash and Uncle Ikes pot shop sit on either side of a well-established African American church, Mt Calvary.

Across the street, theres a store that sells $4,000 electric bicycles, soon to be joined on the ground floor of a towering new apartment building, by a Brooklyn-esque barber shop/artisan coffee bar.

Im no expert, but those sound more gentrifying than a car wash, says the owner of both Sea Suds and Uncle Ikes, Ian Eisenberg.

Others in the neighborhood would disagree. Uncle Ikes, which opened in 2014 and sells pot for as little as $10 a gram, has become a symbol to them of the growing displacement and runaway affluence in the Central Area.

Mt Calvary has tried, unsuccessfully, to shut Ikes down on account of its operating too close to the churchs teen center. And in April, some 100 protesters picketed the pot shop, acutely aware of the irony of a white-owned business making millions from the legal sale of pot when, as longtime Central Area resident and activist Pamela Banks puts it, Black and brown people are still sitting in jail who sold weed on that corner.

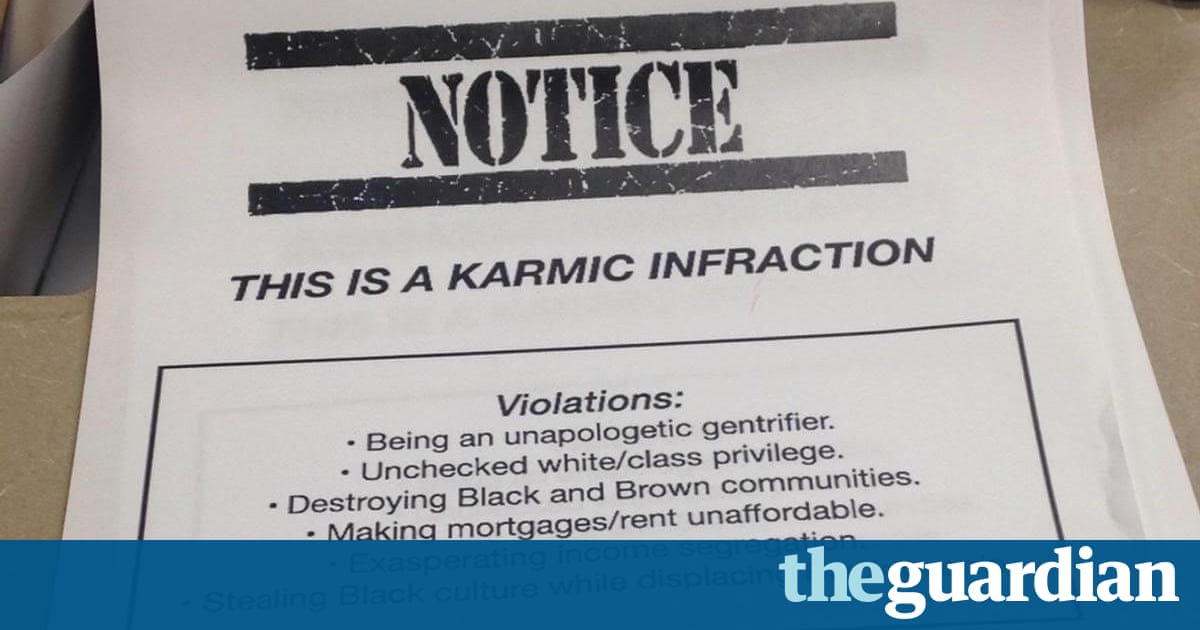

But last week, Uncle Ikes, CommuniTea Kombucha and the new apartment building, the Central, became the targets of a quieter, more unconventional protest: Emnet Getahun, a 25-year-old daughter of Ethiopian immigrants who was raised in the area, and her Cuban cohort, Yeni Lopez Sleidi, taped up black and white, wanted-style flyers on the properties. The karmic infraction leaflets accused the shops of being an unapologetic gentrifier, exasperating income segregation, making mortgages and rent unaffordable, and destroying black and brown communities.

A video posted by Yeni Lopez Sleidi (@real_person_with_feelings) on

My parents were able to build a life for themselves and start a small business in the 90s, says Getahun, whose folks once ran a small cafe in Seattles Rainier Valley. If they moved here today, that would not have happened. My entire economic foundation was because there was affordable housing in Seattle.

Speaking of Uncle Ikes, she says, Its development thats not wanted. Its ignoring the request of that community.

In a recent interview with The Stranger, Sleidi said the duos intent was to disrupt [the] comfort of the targeted entrepreneurs.

But Chris Joyner, who owns CommuniTea Kombucha, rejects that picture. Im not, by any stretch of the imagination, wealthy, he says. He adds that his business, which relocated from nearby Judkins Park a year ago, has buried him in debt, and that he moved into an existing 1929 building, while developers would have reduced it to rubble. Pointing it at me is a little silly because of who I am and what Im doing, but I realize its symbolic.

Banks, the head of the not-for-profit Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle, laments the fact that her gym, dry cleaner and beauty-supply vendor have all recently closed or moved, and fears for her local supermarket, Promenade Red Apple, now that Microsoft cofounder Paul Allens Vulcan Real Estate has purchased the property it sits on.

Michael Moss, whos managed the store for 25 years, is cautiously optimistic about its prospects, saying Vulcan has made it clear that they want Red Apple here. But economics can often trump the best of intentions.

My wife and I just came back from San Francisco its the perfect model for whats happening in Seattle, says Moss. Techies are coming in to work at Amazon and they need to provide housing, and theyre pushing people out. Theyre taking it to a level thats just out of control. Youre putting in eight townhouses where there used to be just one little house, and theres no parking. Back in the 50s and 60s, there were jazz clubs and now theyre gone. Its losing its flavor.

African Americans used to be 80% of our business; now theyre only about 30%, he continues. The majority of our customers are 25- to 35-year-old white people. A lot of the items weve had to integrate into our stores have been natural or organic. (The store still stocks pig ears, however, even though theres no profit in it, says Moss.)

Still, other small businesses see the neighborhoods changing ecosystem which, most poignantly, saw a longtime African American newspaper, the Facts, give way to PLAY Doggie Daycare as nothing but a good thing.

Theres less crime, says Amelework Chalachew, who helps her mother run Cafe Salem, an Ethiopian restaurant thats been in the Central Area for 14 years. We dont see as many crazy people walking around all the time. We feel a little safer taking the garbage out at night.

Through the end of the 20th century, the Central Area served as Seattles undisputed center of black culture. But as the city boomed economically, the neighborhoods black population thinned out. Some longtime homeowners cashed out and moved to the suburbs, yielding to more affluent caucasians who didnt want to drive two hours to get to their jobs, Banks says. Today, the neighborhood is majority white.

Still, there are many visual reminders of the Central Areas black heritage. A stretch of Yesler Way is named for the jazz great Ernestine Anderson, while a performing arts center bears the moniker of the slain civil rights leader Edwin Pratt. On the wall of a chicken and waffles restaurant owned by an Italian man, but managed by a black woman who grew up in the neighborhood on Martin Luther King Jr Way is a meticulously restored mural of the hero himself.

African motifs are well and good, but if black and brown people cant afford to live here, whats the point? wonders Banks. Youre memorializing our history, like: Black people used to live here. Thats an insult to me. Theyre giving us all these landmarks, but theyre not preserving the people.