‘A pivotal moment in the west’: pro-militia Oregon sheriff seeks re-election

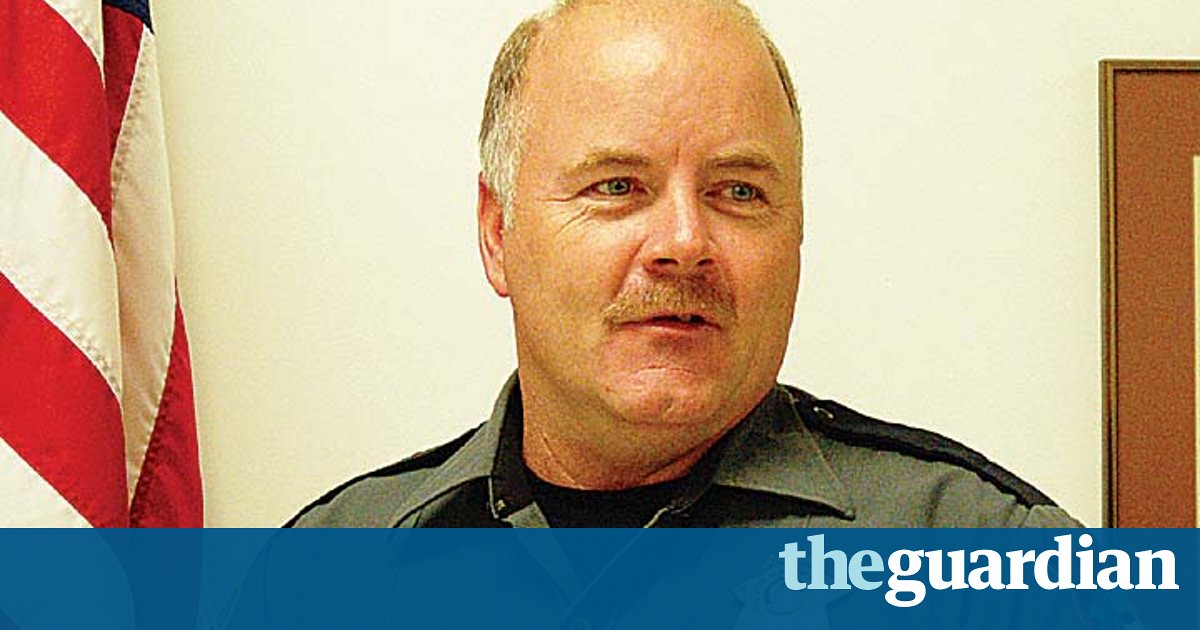

Glenn Palmer, a three-term incumbent linked to the Patriot movement, is among the wests most controversial local officials and could stay in office after Tuesday

Theres an election on Tuesday, and voters in Grant County, Oregon, face a stark choice. They have to choose their sheriff, and the result of that race will resonate far beyond the county. Many observers will see it as a referendum on the gains made in the west last year by the Patriot movement.

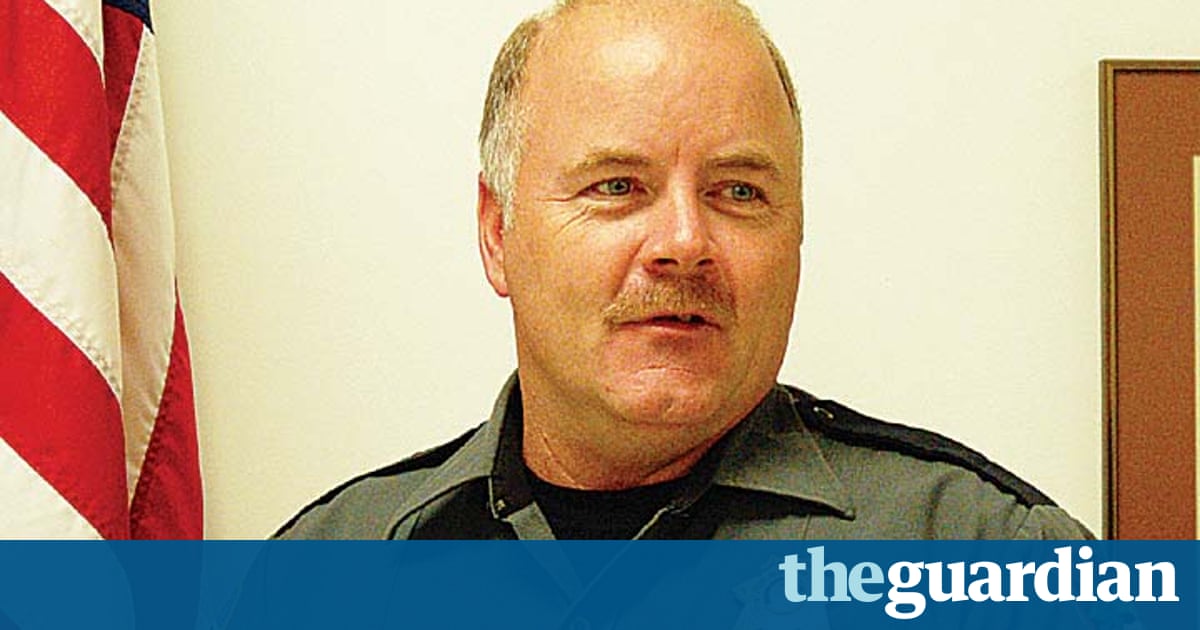

Just as in the presidential race, those involved see it as having an almost existential significance. This is a pivotal moment in the history of Grant County, and the entire west, says Todd McKinley, the wiry, clean-cut contender whos hoping to dislodge the three-term incumbent, Glenn Palmer.

The Guardian spoke with McKinley in a coffee shop in the main street of John Day (population 1,707) . He chose a window table at the far end of the coffee house. When told that other interviewees had asked to meet here, he said with a smile, Its a good spot. You can watch your back.

Even more than in other small towns, people here seem to have a sense that they are being watched and listened to closely. Some feel the need to hold their political opinions close to their chests.

Not so for McKinley, who has spent his whole policing career in the Grant County sheriffs office, working alongside his opponent from 2001 onwards. But over the years, his relationship with Palmer grew strained, due in part to his former bosss unusual political connections with the Patriot movement, which refers to a range of anti-government groups, including militias, tax protesters and so-called sovereign citizens.

I believe the sheriffs office [should be] more about policing and less about politics, he said.

This year, Palmer has become one of the most controversial local officials in the west after his support for constitutionalist and militia groups became a topic in Oregons media, as well as the subject of complaints by those working alongside him.

After a group of armed men led by Ammon Bundy occupied the Malheur wildlife refuge in neighboring Harney County on 2 January 2016, this remote corner of Oregon became the center of a national story. Palmer praised them as Americans and patriots in local media and argued that the government was going to have to concede something.

When members of the Malheur occupations leadership were finally arrested on 26 January, they were on their way to John Day to address a public meeting, which Palmer attended. One of those leaders, Lavoy Finicum, was shot dead after he left the car and appeared to reach for a sidearm. Among his last words were: Im going over to meet the sheriff in Grant County.

Earlier in the occupation, on 12 January, two occupiers anti-Islamic activist John Ritzheimer and Ryan Payne, alumnus of the 2014 Bundy ranch standoff in Arizona met with the sheriff at a group lunch in John Day. Ritzheimer told reporters at the time that Palmer had a practical plan for helping unravel the federal government, and that he had asked the two men to autograph his pocket constitution.

During and after the occupation, Palmer received pushback from a group of local residents, calling themselves Grant County Positive Action, who organised protests against the occupation and took out ads in local newspapers demanding that Palmer explain his actions.

John Days 911 dispatch manager, Valerie Lutrell, wrote a complaint to Oregons department of public safety standards and training about Palmer, in which she mentioned the support he was showing for the militia occupying the Malheur refuge as well as his disregard for the potential consequences of pushing his personal agenda. She also claimed that he was viewed as a security leak by his own staff, as well as local and state authorities.

This complaint and others triggered an ongoing investigation by the Oregon Department of Justice into allegations against Palmer, including tampering with police records.

So far, Palmer has avoided publicly detailing the precise nature of the relationship he had with the occupiers. He has fought attempts to get access to his email exchanges with the Bundys during the occupation. The sheriff has long refused to speak with local outlets such as the Oregonian, and reportedly threatened its reporter with legal action for attempting to contact him.

Indeed, hes not inclined to explain himself publicly at all.

The Guardian repeatedly endeavored to speak with him about the election with in-person visits and phone calls to his office. Palmers only response was a curt no thank you to an email request.

The Malheur standoff revealed just one dimension of Palmers relationship with the so-called Patriot movement. He has also had a long association with the Arizona-based sheriff Richard Mack.

Mack founded the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association (CSPOA), a group resolved to assert the authority of local sheriffs in the face of any federal attempt to register or seize firearms, arrest or search individuals, or use military force against citizens. They argue that federal agents should not arrest people or seize property without first notifying and obtaining the express consent of the local sheriff.

In short, they believe that the county sheriff is the highest legal authority in the land (they even claim that the power of the sheriff even supersedes the powers of the president). In that, they share the same basic hostility to the federal government, and the same reading of the constitution, as the Malheur occupiers.

Mack is also a board member of the Oath Keepers, a group founded in 2009 whose goal is to defend the constitution and in particular the second amendment right to bear arms against what they see as federal government overreach.

More disturbingly for locals, Palmer has according to local press appointed 65 special deputies far more than any other Oregon sheriff who report directly to him. In the letter of complaint written by Lutrell, the 911 dispatch manager, she complained that Palmer had provided no list of the people he had deputized, but had said that anyone that I deputize should be given access to the towns dispatch systems.

Odd incidents have been reported involving these special deputies. In October 2015, according to Lutrells letter, Palmer asked a forest service officer to release a man he had detained because he was a special deputy. In September this year, another deputy shot a dog in the street in Canyon City, saying it had attacked her.

Because of this lack of transparency, some local residents were not willing to be named after talking to the Guardian, fearing possible intimidation.

One who is less reticent is Dan Becker, a local McKinley supporter who has retired from the US Forest Service.

Theres a lot of anger here, he says of his community, explaining that Palmer, his local supporters, and his Patriot connections are trying to harness it. For them, this is Lexington or Boston Square. This is their moment to take back what they believe America has lost or left behind. Theyre serious people.

Like other local residents the Guardian talked to, he emphasizes that Palmers hardcore supporters are small in number the inner circle is around 20 people, including some outsiders drawn to Grant County by Palmers reputation.

And their biggest opportunities seem to arise from disaster.

Palmer knows whats right and wrong

On 14 August 2015, the Canyon Creek Complex became one of the most destructive wildfire in Oregons history.

In a few hours it gutted 43 homes and incinerated numerous cars, RVs, and outbuildings. It burned up 110,000 acres of giant Ponderosa pines and Douglas firs in and around Grant Countys share of the Malheur national forest.

Of those events, McKinley says: I ran the operations. We got it done and we didnt have a life lost.

McKinley says the success in preserving local lives is evidence that cooperative relationships between between county and federal agencies help everyone. But the trauma of lost homes further soured local politics, and many ended up blaming changes in the US forest services fire management practices. Old school strategies such as thinning out trees with logging and clearing undergrowth have become less prevalent as environmental values have exerted greater influence.

In August 2015, the Guardian was present at a meeting in neighboring Prairie City at which US Forest Service officials who were preparing the community for possible evacuation were subject to sustained, hostile questioning from some residents about fire prevention.

This blame game played into the hands of Palmer and his tight group of local, rightwing allies, who, in keeping with Patriot movement ideology, see federal land management and ownership as a usurpation of local prerogatives.

Specifically, according to a report by the social justice thinktank Political Research Associates, Palmer and other Patriots adhere to a particular doctrine of coordination, which is interpreted by those hard-right groups to give local governments an equal position at the negotiating table with federal and state government agencies.

After the fires, in September last year, Palmer deputized 11 Grant County residents to draft a natural resources plan for county-level land management. Such a plan, developed outside county processes, is in keeping with Patriot tactics of establishing bodies which are intended to function as shadow governments pushing their own agenda.

The plan calls for negotiations between the United States and the county on a government-to-government basis in determining public land use, not mere consultation. This means the county is seen as having equal or greater authority than the federal government.

One of those deputised to write the plan was Jim Sproul, of Prairie City.

Sproul told the Guardian that the plan was intended for use in the coordination process, which is federal law and allows local government agencies to have a meaningful say in these land use decisions. Sproul describes the writing committee as a citizens group, adding that Glenn [Palmer] supports us 100% because he knows whats right and wrong.

The group was small, though, and neither elected not formed by any recognized process. Members wanted to put it to a ballot, but county commissioners rejected it.

Still, Sproul believes that if the plan were put to a ballot, it would be successful adding: Thats why youre seeing so much of a push against our sheriff. He claims the plan was shot down by commissioners because of the power of the existing consultative management body, Blue Mountains Forest Partners.

Like his plan, Sproul thinks Palmer will prevail. Hes a constitutional sheriff he represents the people, all of the people. Hes a damn good sheriff, hes well liked, he will win this election.

He says Palmer edged McKinley out of the sheriffs department because Todd has a problem with authority. He doesnt follow orders, pointing to his political disagreements with Palmer.

McKinley says: I find it interesting that [Sproul] is accusing me of having an issue with authority when he was supportive of the Malheur occupiers.

The natural resources plan was the culmination of a longer history of conflicts between Palmer and the federal government. In 2011, he terminated a contract with the Forest Service which had seen deputies patrolling federal land in exchange for payments and the use of Forest Service facilities, such as a search and rescue helicopter.

In his own letter terminating the arrangement, Palmer cited Article I, Section 8 of the US constitution, which in part reads:

The federal government shall exercise authority over all places purchased by the consent of the legislature of the state in which the same shall be, for the erection of forts, magazines, arsenals, dock-yards, and other needful buildings.

Many in the Patriot movement believe that these are the only purposes for which the federal government can acquire land. National parks, forests, wildlife reserves and public land are, they believe, simply unconstitutional.

It is also the same fragment quoted by the occupants of the Malheur national wildlife refuge to underpin their demands that the federal government hand over control of public lands to counties.

Unemployment in the timber belt

Palmers letter also cites socio-economic issues as a reason for breaking off the agreement like the Bundy group, Palmer attributes the long-term decline of Grant County, and by extension the western interior, to the refusal of federal agencies to allow unbridled economic exploitation of public land.

A public break between Palmer and McKinley arose from the latters decision to write a letter to the local newspaper disagreeing with the sheriffs decision not to renew that contract. Palmer put him on administrative leave.

The truth involves a bigger story. Grant County is in the timber belt, an area stretching from northern California to Washington which has suffered from the disappearance of logging and milling jobs over the last four decades.

Almost every county in rural Oregon has shown some degree of recovery from the depths of the last recession. But according to figures from Oregons office of economic analysis, employment in Grant County peaked in 1992, and is still around 15% down on 2003, with very few signs of improvement.

Whereas some timber belt towns have increased in size as retirees and others move in, Grant Countys demographics look a lot more typical of the rest of rural America. In 1980 there were 8,210 people there; in 2035 its projected there will be just 6,785, while Oregon as a whole will have practically doubled its population to almost five million over the same period.

Grant County is still dependent on its remaining timber mill as a private sector employer, but the future may be even bleaker than its immediate past.

Environmental protections and more stringent management of public lands have played some role in this, but only some more efficient milling, cheap imports, the disappearance of the low-hanging fruit of old growth timber, and the decline of the US labor movement have also badly affected the logging industry.

This complex misfortune heightens the temptation to blame federal agencies for local problems, says McKinley. Theres less logging, unemployment people want to blame someone, so they blame the Forest Service.

According to Becker, the disappearance of timber jobs from the 1980s on led many unionised, Democratic-voting mill workers to leave town. This tipped the balance further toward conservatism in a now deep-red county.

Glenn Palmers politics, though, go beyond mere conservatism. Hes part of a gathering movement that wants to challenge the very idea of federal public lands, and Democrats have few incentives to challenge such candidates in conservative areas.

Some of Grant Countys problems come down to the fact that is it a long way from anywhere but versions of this political dynamic are visible everywhere, to the extent that they have come to define the political landscape of 2016. In the face of change and decline, Palmer, politicians like him throughout the west, and the Patriot movement as a whole are offering their own version of the promise to make America great again.

There arent any polls in Grant County. We wont know until tomorrow whether its people have finally decided that those promises are hollow.