Epicentre of learning: the dairy farm teaching scientists how earthquakes form

A farm in New Zealand with an active fault line running through it has become a mecca for geologists seeking to unlock secrets deep underground

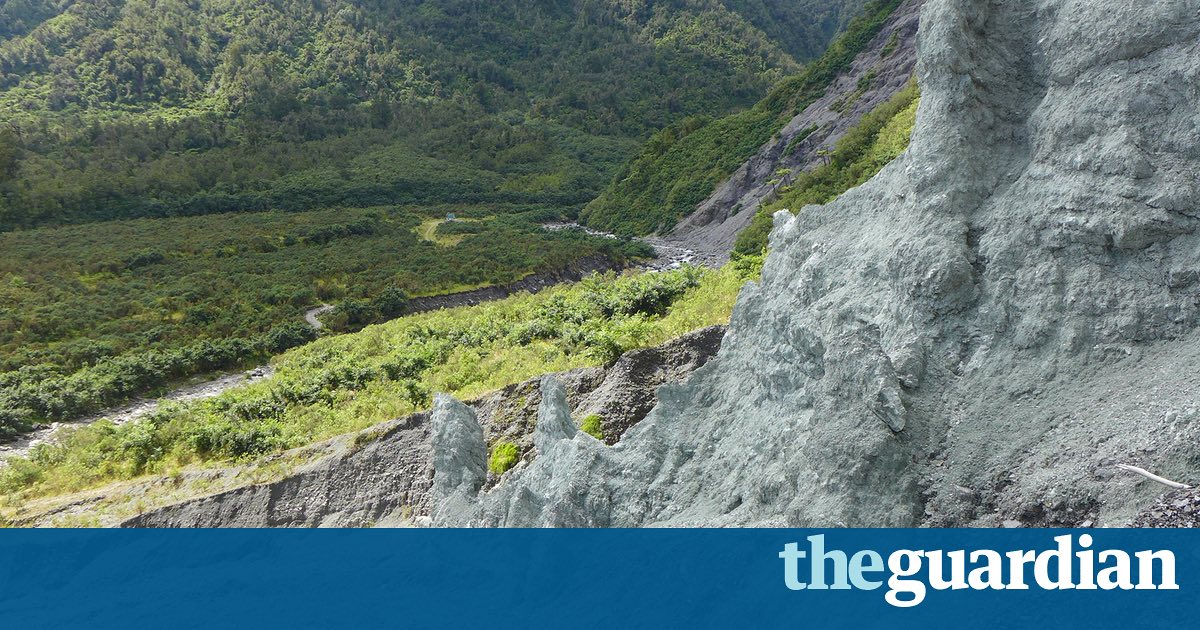

When dairy farmers Gray and Vicki Eatwell purchased a block of farming land just outside the tiny west coast village of Whataroa in New Zealand, the real-estate agent gestured vaguely at a cliff of striking, green-tinged rock on the border of their property at Gaunt Creek.

She said: Thats the alpine fault, the meeting of the Australian and Pacific plates, says Gray Eatwell. But we thought no more of it, locals were blas about it. I had no idea my whole life would become about that rock.

With one quiet pub and only a few hundred residents, Whataroa is an easy place to overlook. But to scientists around the world Gaunt Creek invokes a sense of wonder, as every year dozens of top international geologists descend on this remote stretch of coast to study the temperamental fault.

Although it is not unique to be able to physically view fault lines that have cracked through the earths crust, they are unusual and hugely important to science.

Geologists agree that the site at Gaunt Creek, where they have set up a seismic observatory and embarked on an ambitious international drilling project involving more than a dozen countries, is one of the best in the world.

It is a very special place, and it has always been famous among the international geological community, says Hamish Campbell, a geologist and palaeontologist for GNS science, who estimates he has visited Gaunt Creek more than 20 times during his career.

But it wasnt until the recent earthquakes that there has been a quantum leap of interest in the alpine fault. When I was a student in the 1970s I went to Gaunt Creek and thought it was static and irrelevant because we didnt think or know it would move again. Now our knowledge has exploded exponentially; and we have learned the alpine fault is due to move again soon.

The alpine fault runs for 500km (310 miles) along the western side of the South Island from Milford to Marlborough and is visible from space.

The fault has fascinated geologists for decades, as it is a notoriously active, and predicted to erupt every 330 years, producing large earthquakes of magnitude eight and above.

The site is particularly important to scientists because of the easy access it allows for drilling into the fault and for the rich array of rocks brought to the surface from the depths at which earthquakes nucleate (about 6 to 12km underground) which are crucial for understanding why and how earthquakes form.

The exposed section of the alpine fault at Gaunt Creek emerged sometime in the 1950s, and the last recorded major rupture was in 1717 which means the fault is late in its cycle, and due to rupture again.

Although the fault has always been of significant interest to the scientific community, it wasnt until the devastating 2011 Christchurch earthquake which killed 185 people that the New Zealand government snapped to attention – and funding poured in for further study.

Recent visitors to the site include professor John Ludden, executive director of the British Geological Survey, Dr Chris Pigram, CEO of Geoscience Australia and Yusako Yano, deputy director general of the Geological Survey of Japan.

It is absolutely exciting when youre there, to be able to stand with one foot on either plate, says Julian Thomson, an educational outreach officer for GNS Science.

It is a reminder of the complex dynamics occurring beneath our feet.

When the Eatwells moved into their farm in 2011 they were looking forward to a gentle slide into semi-retirement at least that was the plan.

But scientists kept knocking on their door, asking for permission to cross their land to access and study the fault. Gray Eatwell who has a life-long interest in the formation of New Zealands southern alps began tagging along on these expeditions and helping the scientists with practical tasks such as ferrying equipment across the local creek.

Their excitement was sort of contagious, he says.

We started sitting in on the lectures the scientists would give their students, and then they gave me some written material. When you have the top people in the world clamouring to come through your backyard, you cant help beginning to think what we have here is pretty special.

In 2011 and 2014 teams of geologists from 14 different countries descended on Whataroa for the Deep Fault Drilling Project. They ate whitebait patties and steaks at the Whataroa hotel, slept in simple cabins and rented houses and mixed and mingled with the local farming community.

Scientists are not quite the same as us but we [the town] got a good vibe from them, says Vicki Eatwell.

In 2014 the Eatwells decided the alpine fault was too interesting to limit to a select group of scientists, and they launched Alpine Fault Tours, buying a four-wheel drive bus and setting up a shop on the main street.

Many New Zealand geologists have been supportive of the couples unusual venture, donating time and resources to helping them launch their first foray into earthquake tourism.

If anyone had told me Id be doing this, I would have said they had rocks in their head, said Gray Eatwell, who leads the tours, sharing knowledge he has amassed after years of sipping billy-tea by Gaunt Creek with some of the worlds best geologists.

But the more you learn about it, the more interesting it gets. We have dedicated ourselves to making it [the fault] available. When you see the magnetic effect it has on people, it keeps you going.