Gnter Grass: When the time comes, we will rest on leaves

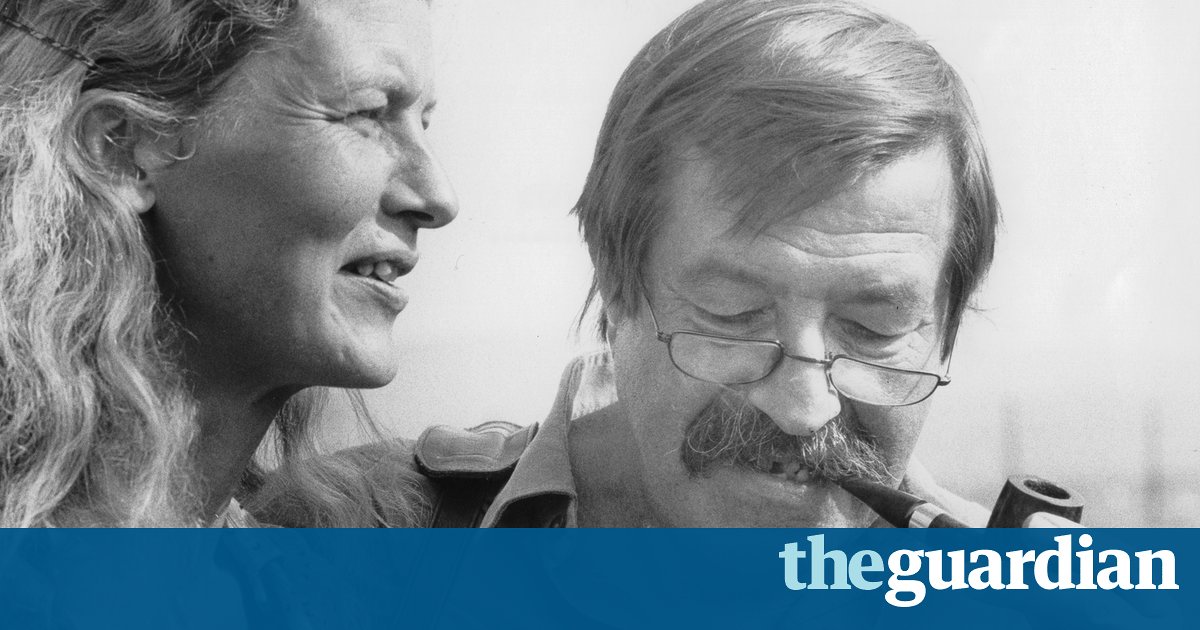

An exclusive extract from the Nobel prize-winning authors final work describes how he and his wife imagined their farewell

At long last, having discussed our joint project many times, testing and rejecting various ideas at the kitchen table, we had reached a decision; the master carpenter Ernst Adomait sat across from us. The conversation began over tea and cakes, hesitantly at first, but soon underway.

Adomait has worked for us for years. Hes built standing desks and bookcases, and various smaller items for my wife. We told him what we wanted, never defining it as our last will and testament. After looking through the French window into the summery, windless garden, he agreed to take the job and make the boxes. He suggested they be measured separately for length and width, and we agreed. He had no objection to our request for two different woods: pine for my wife, birch for me. The boxes would be of equal depth, but hers would be two metres 10 long and mine two metres. My box would be five centimetres wider, to match my shoulders.

When I said not tapered toward the foot, which was once standard and may still be customary, he nodded in agreement.

I mentioned Wild West films in the course of which this sort of plain carpentry grew in demand. My sketch on a paper napkin proved unnecessary; the idea was clear enough. The boxes would be finished by autumn. We assured him we were in no hurry, but laced the conversation with hints about our combined age.

The style of the handles was still under discussion. I wanted something in wood. My wife favoured strong linen straps. In any case, there would be four on each side, to match the number of our children. The way the boxes would be sealed was left open for the time being. The conversation was down-to-earth at first, and dealt with practical details, but soon turned almost cheerful. When I suggested setting the lids loosely on top after all, the weight of the earth will hold them in place or fastening them down with carpenters glue, Adomait permitted himself a quickly fading smile, then declared pine and birch dowels more suitable.

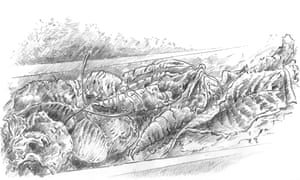

A costly method, he warned. Alternatively, screws could be inserted in carefully drilled holes. I favoured hammering in old-fashioned nails with solemnly resounding blows at a given signal. In the postwar years, I often put up gravestones in cemeteries while working as a stonemason, and once made a deal with a gravedigger: five Lucky Strikes for a good dozen hand-forged coffin nails; later, much later, they appeared as rusty assemblages in drawings, lying this way and that, a few crooked, each with its own shape. And every nail had a tale to tell from its past. Sometimes I added dead beetles lying on their backs, and bones large and small. In one drawing, nails and rope hinted at a death only humans could devise. Soft pencil, hard-line pen and ink drawings, all of them still lifes, a few found buyers intrigued by their cryptic nature.

Adomait seemed to follow my digressions more out of politeness than interest. Then we chatted about current affairs: the ludicrous rise in the price of petrol, the uncertain summer weather, the now-familiar bankruptcies. I set a bottle of mirabelle plum brandy beside the empty teapot and what remained of the cakes. Just a small glass, said the master carpenter, who still had to drive home in his truck.

By the time Adomait left, wed decided on wooden dowels and rough linen handles on each side of the boxes. We can count on him, my wife said. He has always delivered on time. The interior decoration of the boxes hadnt come up that afternoon, since it didnt involve carpentry. The only thing we were sure of was that padded upholstery, cotton or down, was out of the question. That sort of expense might be customary in commercial coffins, but we werent looking for comfort.

It was only at breakfast, after my usual complaint that my mattress was too hard, and when the dishes had been removed and the tabletop was bare, that an idea came to me, somewhat vaguely at first, but soon assuming a clearer shape. I suggested that after the obligatory washing of our lifeless bodies, we be laid to rest on a bed of leaves, then covered with more leaves by our daughters and sons, using whatever Nature offered, according to the season. In spring, budding leaves would cover us; in summer, fruit trees cherry, apple, pears and plums could lend their lush green, mature abundance. Autumn, my preferred season, would make its brightly coloured offering. And dry, rustling leaves could deck our naked bodies in winter. The old walnut tree, the copper beech, the maple would provide variety. A handful of walnuts could adorn our leafy cover as an extra feature. Only the two chestnut trees outside our house, sickly for years, would be forbidden to add their rust-afflicted foliage. I also requested there be no oak leaves.

At any rate, when the time comes we will rest from head to toe on leaves and be decked with leaves. At most our faces will be free, perhaps with rose petals on our closed eyes, a custom I witnessed during our stay in Calcutta: there I saw some young men trotting along, carrying the body of an old woman on a bamboo pallet to a cremation site on a tributary of the Ganges. Bright green leaves were pasted over her eyes.

In addition, my wife chose not to forgo a shroud one she said she would sew herself.

That seemed preparation enough. Over the course of a time no longer ours, all would decay, the box and its contents. Only bones large and small, the ribs and the skull might remain, unlike the bodies buried in the bog in Schleswig-Holstein, now placed on show under glass in the Schloss Gottorf Museum. Those bones turned soft; you could still see tissue, skin and knotted hair, as well as bits of clothing, relics of a ghastly prehistoric age, of scientific value, eagerly sought as fodder for bog-bodies stories, like the one of a young girl whose face was covered with a strip of cloth in punishment for some atrocity that could scarcely be imagined.

The skull, on the other hand, has always harboured a rich store of meanings, from the ingenious to the ludicrous. Piled high or fitted into walls, skulls rest in the vaults of monasteries. A skull adorns the pirates flag, serves as the logo of a soccer club. It signals a warning on cans of poisonous, explosive or flammable material and appears as a motif in the fine arts, in oil paintings and copper engravings like the one by Albrecht Drer showing Saint Jerome in his study. Withdrawn from all worldly concerns, he bends over his books, while the fleshless skull beside them reminds us of the transience of all living things, that from birth on, death is a settled matter.

But we werent that far along yet, in spite of our increasing frailty. The planks for the boxes wed ordered could be cut to size, but a few questions were still in the air that were harder to answer: what carpenter would build a refuge for the wandering soul, whose existence we both desired and doubted? What facade would reach high enough for the climbing ivy of immortality? How might we be reborn, as worm, mushroom, or resistant bacteria? What other beings might inhabit the void?

In addition to ivy, we could spend a rampant afterlife as weeds no gardener could control. And what of creatures that creep and fly? With Natures all-powerful help, Ive always hoped to be reborn as a cuckoo, drawn to the nests of strangers. One year after another holds great promise. Even leaving God and his promises aside, speculations remain that wont fit in our boxes. Only the transitory nature of their contents can be guaranteed: the rigidity of the corpse; the greenish-blue discolouration of the skin, gassy, bloated and soon bursting; the onset of mould and all the other signs of rot; the worms.

Things we still need to think about the final question: where should we be laid to rest? A good 30 years ago, when we were living in the city and first thought of looking for a plot, I favoured the cemetery in Friedenau. But my wife had something against Berlin as our final station. In the end I did too, since soon after the wall fell, the citys claim to be the nations capital gave rise to too many shiny bubbles of loudmouthed boasting.

Having moved many times, we considered various cemeteries with Lbeck as a cosy backdrop but reached no decision. One near the railway station, where you could sense rows of graves hedged by boxwood trees, would have matched my endless longing to travel. But since we wished to be at rest, a double grave in our garden, between the studio window of my workshop and the shed, with nothing but the woods beyond, would have been our preference. But in spite of our countrys solemn canonisation of private property, burial on ones own land is forbidden by law. Cremation remained the only way out, followed by a fake theft of the urns by our sons, so our ashes could eke out their shadowy existence behind the blackberry hedge or in the lilac bushes. But having no wish to deny the worms our mortal remains, we decided against ashes and agreed to talk with the pastor of Behlendorf about making the local village cemetery our final address. A meeting was easily arranged. The pastor, who turned out to be quite affable, if somewhat overburdened by the spiritual welfare of his current souls, understood our aversion to resting among the rows of graves, since as individuals and newcomers we were unfamiliar with the neighbourly or familial entanglements of the villagers at rest there. Even our tactful suggestion that as heathens we would feel out of place near the medieval outer wall of the chancel was, if not warmly received, at least quietly accepted.

We finally settled on a tall, solitary tree off to one side. Beneath its spreading branches I paced out a rectangle the size of a quadruple plot. The pastor told us that this was in an area bordering the cemetery, once a pastoral potato field, unused for some time now, lying fallow, so to speak, although at present it gleamed invitingly as a meadow.

During a pause in the conversation we pictured ourselves lying there, or as the survivor visiting the first to go. As decorative shrubbery I suggested herbs: marjoram, sage, thyme, parsley, anything used in the kitchen. On the eastern edge of the measured quadrangle, an erratic boulder would serve as a gravestone. The stonemason would have the job of carving our names and dates in cuneiform letters. No other inscription or quotation, please. The boulder would have a broad base that asserted its weight without being overpowering.

I paced out the approximate size of the plot again, this time farther from the root system of the tree. Getting the church councils approval for what we wanted, the pastor assured us, would pose no difficulties.

When we got back home, we were a little tired. I treated myself to a coachmans glass of calvados. On the kitchen radio the evening news reported various crises competing for the limelight. According to the weather forecast, rain would continue in the south only. We didnt tell our dog about our successful search for a resting place.

One Saturday in mid-September, after the second pacemaker theyd implanted declined to give my heart the help it needed, and my lungs began to repay me for decades of self-indulgence in handrolled cigarettes and well-stuffed pipes, we were relieved to see the carpenter arrive with the boxes. Ready to use. The look of them, the bright wood, each with its own grain, put us in a good mood. Even Adomait, a serious man on principle, seemed satisfied, and confirmed his mood by attempting a smile.

We had cleared a temporary space for the boxes in the back of the cellar where we kept our garden tools and deckchairs. Plastic covers would protect the boxes from flyspecks and mouse droppings. Seeing them side by side like that reminded me of a special term for coffins from the old East German days: Erdmbel, earth furniture. The eight handles stood at precisely measured intervals. Although well seasoned, the wood smelled new. Without lids the interiors beckoned invitingly.

Before leaving, Adomait did not rule out my now customary offer of a shot of plum brandy in celebration. On top of the bill, which was more than reasonable, he placed a clear bag of wooden dowels for the lids; he had drilled matching holes in the upper rims of the boxes. There were several extra dowels in the sack. As the carpenter had suggested, my wife stored them carefully in a drawer of her desk where, along with the usual odds and ends, she kept our passports, the dogs vaccination certificate and other important papers.

The very next Sunday, with no visitors scheduled, we removed the protective covers, as well as the lids lying loosely on top, took off our shoes, and lay down in the boxes. They were the right length and shoulder width. We made no comment, so solemn was the anticipation of our laying out.

How strange to hear each other breathing. My wife helped me climb back out. When we had replaced the lids on the boxes, we spread the covers over our final homes and gave free rein to our thoughts, which remained, however, unspoken. Shortly afterward, my wife said she was sorry she hadnt taken a picture of me in the box; she would be sure to have her camera with her next time. You looked so content, she said.

Once wed had our trial lie-in, as we called our visit to the cellar, life went on as usual. While my wife was preparing supper two perch with jacket potatoes I sat in front of the TV watching the usual Sunday evening world news with its images from around the globe. When I saw the two fish lying side by side in the pan, with cucumber salad on the side, the comparison seemed so apt I couldnt help joking about it.

The boxes have been waiting ever since. From time to time we remind ourselves how beautiful they are. Im too shy to ask my wife if shes finished sewing her shroud. But I know well have plenty of leaves to clothe and cover us. They will always be available: newly fresh in spring, lush green in summer, brightly coloured from October on, faded and brittle through the winter.

So let another year or two pass. Were not in any hurry. At the moment my pacemaker is doing its job, as promised. Even the children and grandchildren, when they come by for a brief visit and bring up the deckchairs from the cellar on sunny days, have grown used to the sight of our master carpenters custom work.

Lately my wife has started storing dahlia tubers and other flower bulbs in her box for the winter. Next March we hope we will plant them in the flower beds and cover them with fertilised soil from the garden.

Text and graphics copyright Steidl Verlag and Gnter & Ute Grass-Stiftung 2015, English translation copyright Breon Mitchell 2016. Of All That Ends is published on 1 December by Harvill Secker. To order a copy for 10.65 (RRP 12.99) go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over 10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of 1.99.

Read more: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/nov/19/gunter-grass-of-all-that-ends-extract-dying