And if we’re going to stop Ebola in the future, we have to find its hiding places.

Ebola is a zoonotic disease, meaning that it can spread between animals and humans. It burns hot and fast through people. Its ruthless nature means that we are often the end of the line for the virus: a host like us that gets too sick too fast, that dies too quickly, cuts down the virus’s ability to jump into a fresh body. To remain a threat, Ebola needs a safe house in which to lie low and hide.

Such a long-term host, the quiet refuge of a pathogen, is known as a reservoir species. If a reservoir species is Ebola’s safe house, we are its luxury retirement property, a place for it to live out its last days with a bang. The trouble is that we aren’t sure where the safe house is. If we are going to be vigilant against Ebola’s re-emergence, we need to find it.

Bats — Ebola’s hideout?

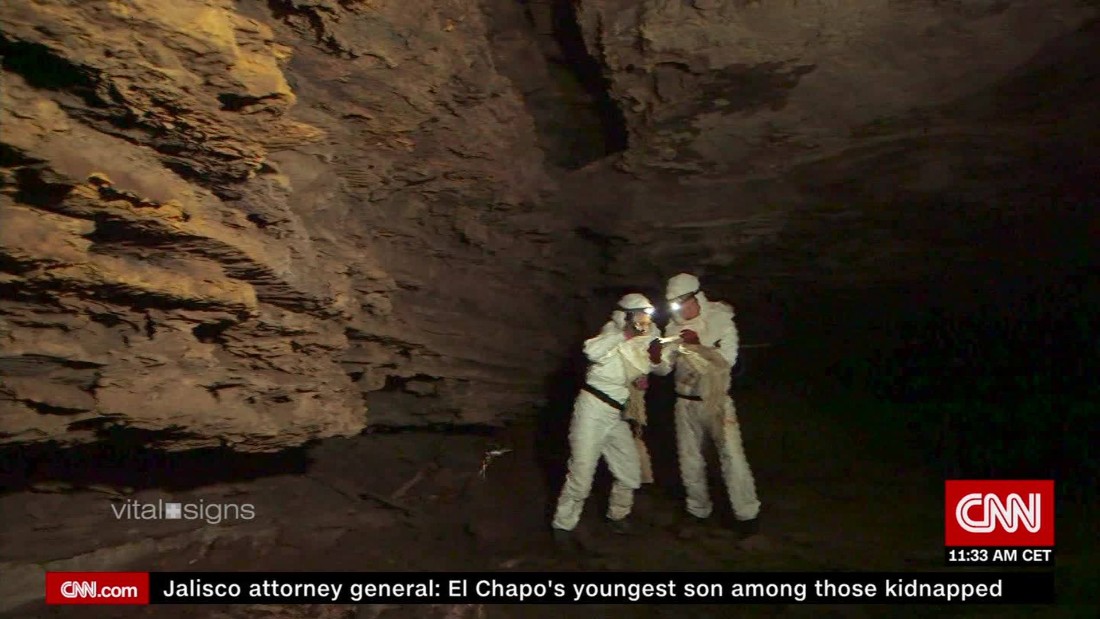

Searches so far have focused on forested parts of Africa, the home of a number of possible reservoirs. Classically, bats have been considered the most likely culprits, given that they overlap with humans geographically and can carry Ebola infection without symptoms. Based on research that has tested a wide variety of small mammals, bats, primates, insects and amphibians, several species of fruit bat have emerged as possible candidates.

A 2005 study published in Nature and helmed by Eric Leroy tested over 1,000 small vertebrates in central Africa and found evidence of symptomless Ebola infection in three species of fruit bat, suggesting that these animals — which are sometimes hunted for bushmeat — might be Ebola’s reservoir. An editor’s summary ran alongside the paper, titled simply: “

Ebola virus: don’t eat the bats.”

Curiously, in Pigott’s model, the presence of bats is not the strongest clue precipitating a spillover event. Instead, he says, the main predictor of where Ebola may emerge is the vegetation index. The amount of vegetation “could influence a variety of different species,” he explains. Though bats were included in the model, “it was vegetation that dominated the profile.” Translation: among areas that had experienced a spillover event, there was a critical pattern of plant cover that stands to be very helpful in identifying areas that might be at risk from Ebola in the future.

Transmission routes

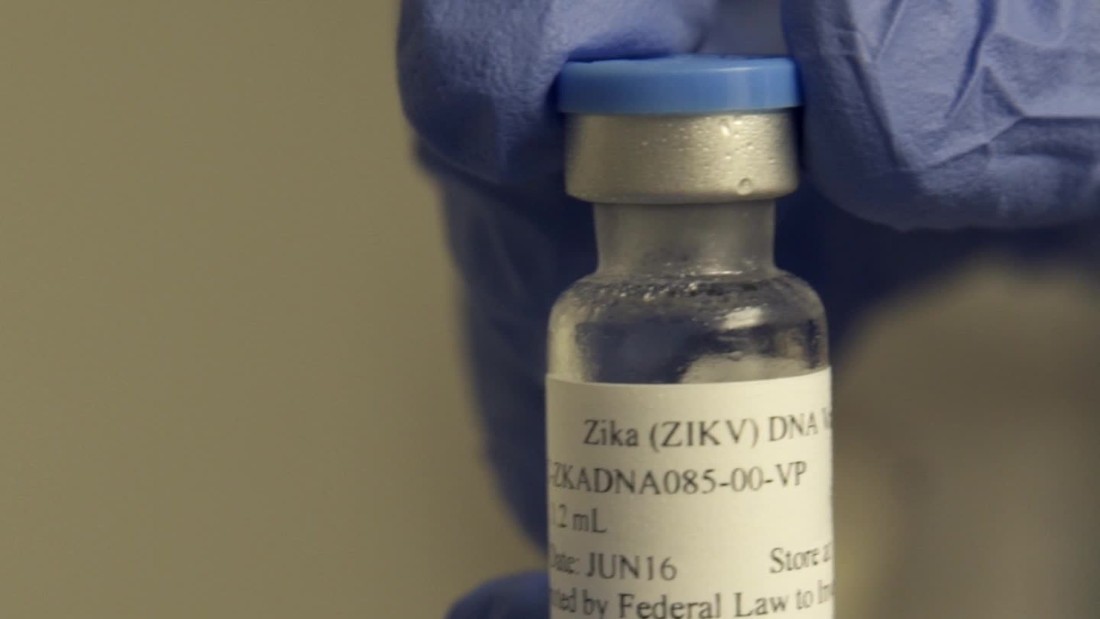

While ecological niche mapping can help in predicting spillover, there’s also another, less well explored hiding place to consider: people. Ebola has an incredible ability, unknown until recently, to stake out a claim in bodily fluids of men who have survived infection, long after they have returned to health.

In fact, a

recent study found that over half of male survivors tested positive for Ebola in their semen one year or longer after they’d recovered, with one survivor’s semen testing positive a full 565 days post-recovery. Because of the risk of spreading infection, male survivors are recommended to avoid unprotected sex until their semen has twice tested negative for Ebola.

Despite this, Pigott thinks it’s worth bearing in mind that most outbreaks historically have followed a narrative of human-animal interaction. “The other big unknown in terms of future outbreaks is how long is the transmission route viable.” It’s hard to incorporate transmission by survivors into a predictive model because we simply don’t know how long people can carry the virus and remain infectious.

This potential for human-to-human transmission means that Ebola has opportunities to re-emerge without a spillover event from the forest. And this means you don’t even need to be near the forest to get it. Ebola’s persistence in semen means we now have to track this curious villain in two ways. We must look for both patterns of emergence in our messy data streams.

So to be prepared for Ebola in the future, we need to discover how the virus moves through the wild and the city alike. We must find out where it thrives and how it spills over, and we must track it to all of the places it goes when we are not watching from the hospital bedside. With Ebola, there remain too many questions for us to rest easy.